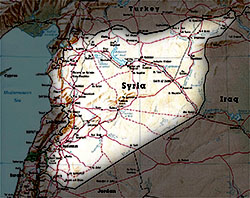

1. How did we get here?The conflict in Syria stems from a long history of civil unrest and unsettling diplomacy. In March 2011, a wave of political protest surged in the nation as rebels of the Arab Spring, a pro-democracy movement currently revolutionizing North Africa and the Middle East, made an attempt to overthrow Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, who succeeded his father’s 30-year reign in 2000. Stimulated by earlier revolutions that had occurred in Tunisia and Egypt, the Syrian rebels requested civil freedom and the release of political prisoners, both of which demanded the resignation of the current dictatorial regime. As reported by The Washington Post, these peaceful protests quickly turned violent when the government responded by massacring and imprisoning the activists and their families.

2. What’s the big deal?

The original protesters quickly began to see their intentions recast into the workings of a full-blown civil war as civilian dissidents organized their defense into armed militias and the state military made an attempt to suppress the uprising by means internationally deplored. Of all the government operations, that which has inspired the most controversy was Assad’s alleged use of chemical weapons in an attack on the Damascus suburbs in mid-August. Later deemed definitive by the UN Security Council, although they did not assign blame, and strengthened by the analysis of hair and tissue samples of victims, the nerve agent sarin was confirmed responsible for the death of nearly 1,000 civilians, as cited by The Huffington Post.

Why all the uproar over a singular incident, you might ask? It all rests on the preservation of international law. In accordance with the 1925 Geneva Convention, the production and use of chemical weapons is prohibited under any circumstances, namely because its principal application targets civilians rather than military personnel and its effects on the individual are thoroughly inhumane. Although the country was absent to the original assembly, the Geneva Protocol was signed by Syria as a declaration of inclusion in 1968. So while conventional weapons have caused the death of thousands in Syria and the detriment reality of this is not unnamed, the fact of the matter is that the use of chemical weapons in particular hold critical weight in the future of “acceptable” warfare, not to mention the legitimacy of UN.

3. Where are we headed?

No one really knows. To intervene or not to intervene is a debate that has occupied Congress from the outset, and for a while had left our nation in a standstill. Talk of a limited air strike among the Obama administration caused widespread contention over the consequences of direct military action and the preservation of democracy, and, according to a CNN poll released on September 9, was opposed by more than 7 in 10 Americans. The executive powers, namely President Obama himself, deemed that such a response would be necessary as Syria had crossed a “red line” in their use of illicit weapons. On September 27, the UN Security Council voted unanimously in favor of a decision to secure and destroy Syria’s chemical weapons stockpile, of which the Syrian government has decided to cooperate. As reported by The Washington Post, the UN convention also advocated plans for a “political transition in Syria adopted by key nations in July 2012” and set a date for a mid-November peace conference in order to facilitate the development. Concerning U.S. future involvement in the nation, an affirmative resolution remains indistinct; while the vast majority of public opinion currently supports diplomacy over militancy as a means to action, there can be no certainty in a situation so complex and instrumental.

![Mr. Abullh Ali, manager/assistant, helps open Queen Yemeni Coffee in downtown Libertyville at 606 North Milwaukee Ave. With the help of employees such as manager and LHS senior Yousef Taha, they are able to bring the Yemeni and Ethiopian culture to Libertyville by using their Queen spices, cinnamon and cardamom in their drinks such as Adani Chai, which is inspired by Sheda, the Queen of Yemen and Ethiopia. “The history of our coffee [is] a long history and we believe that Yemen and Ethiopia started the coffee and we are bringing something unique to the community,” Mr. Ali said.](https://www.lhsdoi.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Photo-1-1200x800.jpg)