The Money Behind Sports

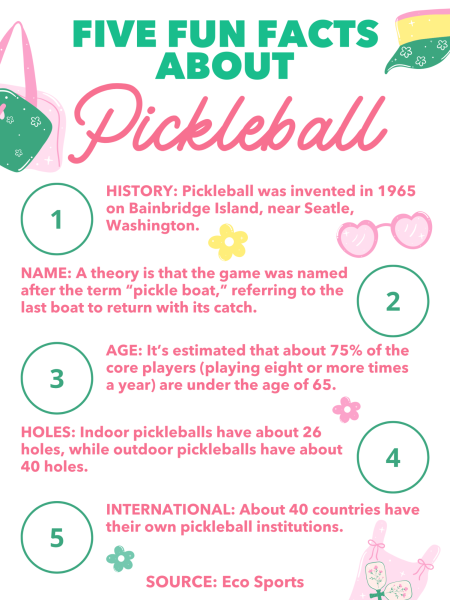

Thousands of dollars are provided annually to each sport at Libertyville High School. People may make assumptions that there are inequalities that exist between how much money each sport is given on a yearly basis, and people may not understand how the budgets are determined and allocated. A more-rounded view of budgets doesn’t come from an analysis of one single year, but rather by looking at the budgets from at least three years, which can show the fluctuations between separate sports.

Over the course of two months, the following information was obtained through research and interviews with the assistance of one of the current LHS interim athletic directors, Mr. Randy Oberembt; former LHS athletic director for 10 years and current associate superintendent for the district, Mr. Briant Kelly; and Mr. Daniel Stanley, the district’s assistant superintendent for finance.

Basics of Budgeting

Excluding coaches’ salaries, for the past three school years, the total sports budget has been in between $440,000 to $450,000 per year for Libertyville High School. Regardless of the change in money given to each individual sport, the designated money spent by the school on athletics each year stays the same. Budgets from the past three school years — 2015-16, 2016-17 and 2017-18 — show how even sports budgets are over a larger time span.

The aforementioned money is provided by both the district and state.

“[On] average, in Illinois, you see about two-thirds [of the money] is local, [about] one-third state and [the rest is] federal,” explained Mr. Stanley. He elaborated, stating that District 128 is different from the average in Illinois: “We get about 3 percent from the state and then maybe 1 percent from the federal government.”

That leaves about 96 percent of the District’s revenues coming from local sources like income tax. Another example of local revenue is the athletic fee. All students who participate in a fall, winter or spring sport pay an athletic fee of $60. All together, the total of all students’ athletic fees combined may seem like a substantial amount of money, but Mr. Kelly clarified that the money mainly just offsets some costs for Libertyville athletics.

The actual budgeting process starts with an annual meeting in January, where coaches and athletic directors meet to decide on how much money a sport will be provided for the upcoming year. Spring sports are budgeted for the following season, without having played their season for the current year. Money is usually distributed by how much the coach requests at that meeting. All of the money budgeted and given is often spent by the coaches in the budgeted year. The money does not carry over for the individual program; all of that remaining money goes to a reserve account, so a coach can’t save money to use the next year.

“[Coaches] have to do a pretty good job of budgeting or thinking ahead, and that’s why it’s the coach and then the athletic director really that will be looking at it,” Mr. Kelly explained.

Equipment Budget

A major part of how much money goes into each sport is attached to its equipment budget. The equipment budget includes money used for supplies, warmups and uniforms, and various sport-specific equipment. Specific sports, such as boys and girls water polo, for example, share some equipment, so they budget together.

According to Mr. Oberembt, certain spikes in data in individual sports budgets can be accounted for by uniform replacement. Uniform replacement consists of purchasing new uniforms for the varsity level and rotating the former varsity uniforms down to the junior varsity (or sophomore level), and so forth. This generally occurs every three years. However, replacement can vary depending on the sport. Some sports buy new uniforms every year because of hygiene and wear and tear reasons, including boys and girls teams for tennis, golf and swim.

A sport’s performance during its season does not affect how much money they receive from the school, said Mr. Oberembt. For example, if a sport wins state one year, the school won’t give them any more money than they need for the next year because they won.

Coaches’ Salaries

Coaches’ salaries are also a huge factor in how much money goes into a sport. Different coaches get different salaries depending on several factors, with one being community expectations. Mr. Randy Oberembt explained how this factor can influence coaches’ salaries: “There are levels of expectations and sometimes [words] that people will use [are] ‘pressure, visibility.’ We could argue whether this is right or wrong, but [there’s] not much argument to whether it’s true or not; in some sports, there’s more visibility. Sometimes that’s accounted for as part of what that job takes.”

A coach will start off with a beginning salary, and then every year they continue to coach, they will get more money until they receive their maximum amount during their ninth year of coaching. After that year, their stipend remains constant until retirement.

For sports larger in size, like football or basketball, a coach might make an average of $10,750 at the end of their nine years, whereas a smaller sport’s coach, like bowling, might make an average of $8,750.

For all sports, there is one coach deemed the head of the program, leaving the rest of the coaches to be considered assistant coaches. Head coaches receive more money than the assistant coaches, however, it is not substantially different.

“Obviously the head coach does get a little more, it’s not much but they do get a little more money because of the responsibilities being the head coach at the level,” explained Mr. Brian Zyrkowski, the head boys basketball coach.

There is no monetary bonus for those sports that go to the playoffs or make it to state.

“I think that’s a good thing [coaches don’t receive additional money for a team’s success] because […] you’re not coaching to get a stipend. Really you’re not. You’re coaching because it’s something you’re passionate about and you want to do,” according to Mr. Zyrkowski. He added that when he previously would coach at a different school and receive no money at all, he was fine with it.

Additional Costs

There are several other costs to a sport that don’t initially come to mind when people think of sports’ budgets.

About $31,000 is set aside for repairs and postage fees. That covers various projects such as new nets for boys and girls water polo, for example. Money that comes from ticket sales at sporting events goes towards an overarching account that pays for these additional costs. Sports that require tickets to enter the game include football, boys basketball, girls basketball on Friday nights, and boys and girls soccer and volleyball during playoffs.

The school sets aside $60,000 a year for officials’ fees, which are paid to all referees, officials and umpires who work sporting events. At all athletic competitions, an IHSA official is required to be in attendance. Compensation to officials makes up 13 percent of the overall budget for the 2017-2018 school year.

Another $60,000 is devoted to transportation and competition fees. Transportation can include the usage of both yellow charter buses, when teams have to hire a separate bus driver for various competitions, as well as the use of white, district-owned buses.

“The way people determine whether they’re taking a yellow bus or a white bus…has to do with the number of kids on the team and also the length of the [competition],” Mr. Kelly explained.

Fundraising

The other money provided to all sports is given through the Parent Cats organization. Parent Cats raises money in general and then later can provide money to the athletic department based on need.

One activity that they undertake and run is the Spirit Store, located near the Main Gym. In the store, they sell Libertyville apparel and accessories, as well as gym uniforms. Parent Cats also organizes the senior Graduation Party, which occurs right after the graduation ceremony.

All other fundraising falls to individual sports and can depend per team. For example, sports like boys basketball, baseball and football have separate booster programs for their sports. Another example of fundraising that’s independent from the athletic budget are the spring-break trips taken by softball and baseball, who separately raise money for these experiences.

Other teams, such as cheerleading, attend an annual summer camp for which they fundraise separately. They also receive assistance from their booster group, the Wildcats Cheer Parents Organization; even with these efforts, students still pay a fee to attend the camp.

On top of all that, activities deemed supplementary and nonessential to be covered by the athletic department are funded separately from the allotted budget. These may include activities such as a team-building events or team t-shirts. Parents also donate or raise money for their teams by hosting pasta parties and providing other food for teams before or after games.

Regardless of where the money comes from and what it is going towards, this larger analysis reveals what comprises the actual sports budgets when all of the different financial categories per sport are taken into account. The money behind sports is compiled from more than just one source and does not only rely on success and community expectations.

![Senior Liam Hanson (1) is escorted by his parents before the game to celebrate senior night. He will miss “hanging out with [his] boys and going out to eat after games and practices.”](https://www.lhsdoi.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/IMG_1389-600x400.jpg)