“Nature and literature are subjective phenomena; every evil and every good thing is a shadow which we cast.”

-Ralph Waldo Emerson, American essayist and philosopher

Perhaps the most nearsighted of grading practices is the designation of language to a strict and finite degree of worth. The method of analyzing student essays (creative or formal) in a way that involves some kind of rubric or other hard-lined device is nearly universally regarded as fair and profitable. While a teacher’s reflection on a student’s work may offer reason, insight and direction towards accepted form, in regards to personal expression, something critical has been misplaced.

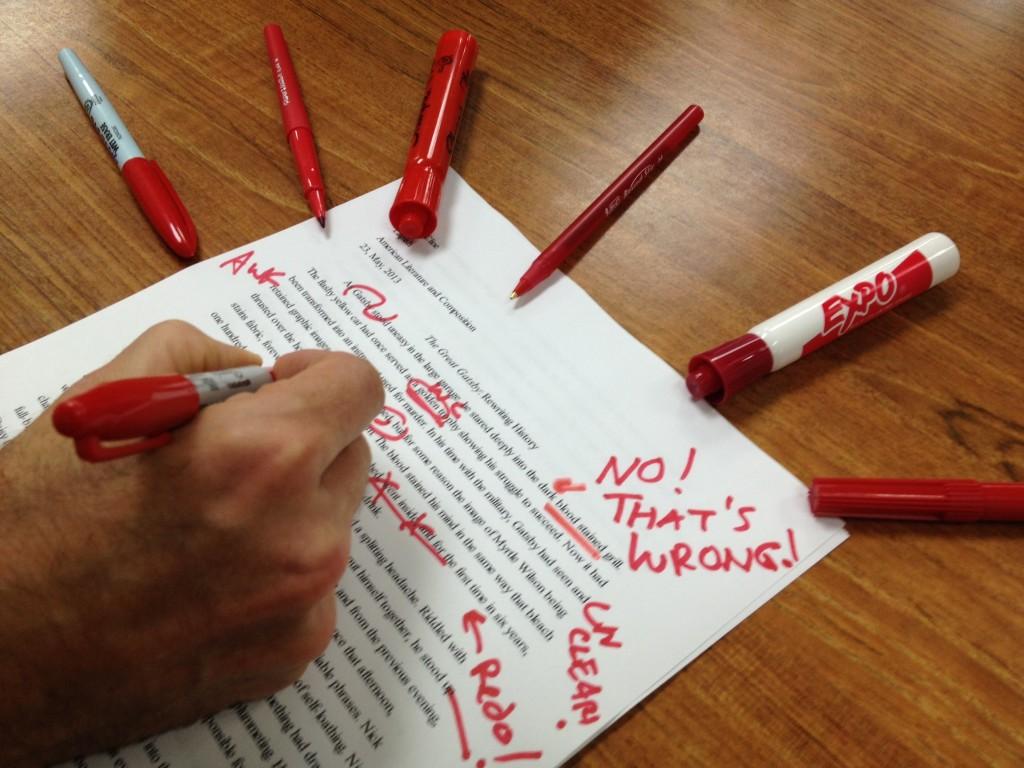

The assessment of written assignments is a system that confounds and frustrates students on a situational basis. In many occasions (but certainly not all), teachers return student essays offering very little commentary, and the commentary that is provided is frequently derived from a biased opinion or personal preferences. But how could one expect otherwise? The evaluation of writing is a wholly subjective process; what one may embrace as genius, another may misread or completely overlook. The recipient of a “below average” score might question the source of his/her error and disagree with the grader’s definition of goodness, but convincing someone that they just “did not understand” is usually a difficult task.

Students, therefore, should not be assigned essay grades on the basis of three substantial truths, each equally as detrimental to the philosophy of composition in theory and in practice.

Essay grades are completely partial.

Just as an individual holds a distinct political belief, so to with literature and the interpretation of its forms. It is not uncommon for a student who had received “excellent” grades in one year of English to find themselves barely passing in the next. Even if the quality of a student’s writing had not diminished, the way in which a particular teacher values written assignments will inevitably reflect on his/her personal standards. I cannot begin to describe on how many occasions I have been forced to adjust and readjust my writing style (thesis statements, organization, depth of analysis) in order to adhere to the expectations of a specific class. That’s not to say that the teacher’s grading student essays are stubborn bigots unwilling to accept anything but perfection;, it’s the fact that something so complex and personal as writing cannot be classified as “good” or “bad” by the views of a single individual.

Essay grades deride a student’s creativity and act contrary to artistic ideals.

Writing in itself is an artistic endeavor, something that requires students to invent ideas and to express these ideas in a profound and original manner. How, then, can a teacher designate requirements for a quality essay? In any case, a student’s creativity is uniquely their own, and forcing an individual to adhere to certain guidelines will inevitably compromise this endowed creativity. Further, disallowing students the freedom to express themselves to their utmost capacity (even if this means rejecting a teacher’s expectations) teaches students to conform to set principles in the future, a concept that completely opposes success in the modern world. Rarely are individuals who have maintained an obedience to common standards regarded as great and memorable;, it is always those who have sought to transcend expectation who continue to be celebrated as innovators. Even a piece of writing that appears insignificant, perhaps for grammatical error or lack of logical organization, should nevertheless be appreciated as an artistic statement, beautiful in its rejection of commonplaces and embrace of unfound disposition.

Essay grades impair students’ analytical ability and the objective of education in general.

In terms of literary analysis, in which one is asked to interpret a text and to forge conclusions as to its significance, assigning letter grades only hinders a student’s development in the long run. By definition, analysis forces one to draw a profound interpretation to a seemingly one-dimensional topic. Therefore, judging any one essay more accurate or acceptable than another discourages an individual’s personal sentiment and insults their capability to understand meaning. Any such degradation will only cause a student to lose interest in the class or to deny their inclinations in the future. And if the goal of education is to accrue to society a youth of innovation and progress, shouldn’t our systems promote unconventional thought and reject defined conclusions?

As Emerson established, the appreciation of writing is by nature inconsistent, and cannot, therefore, be universally understood.