Staff Ed: Can you still be a good person in the 21st century?

Warning: “The Good Place” spoilers ahead

NBC’s “The Good Place” is an American comedy-fantasy series about a group of recently deceased people navigating a highly selective Heaven-like utopia. Its plot is centered on the fact that there is a type of heaven as well as a version of hell, respectively named the “Good Place” and the “Bad Place.” Every action a person makes during their life on Earth is assigned a point value, either positive or negative; these points are totaled when they die and serves as the deciding factor as to whether said person goes to the Good Place or the Bad Place for all of eternity. The point system is designed to work flawlessly—that is, until one character, Michael, notices a glaring error: the fact that no one had gotten into the Good Place for nearly 500 years, which leads him to believe the system is being tampered with.

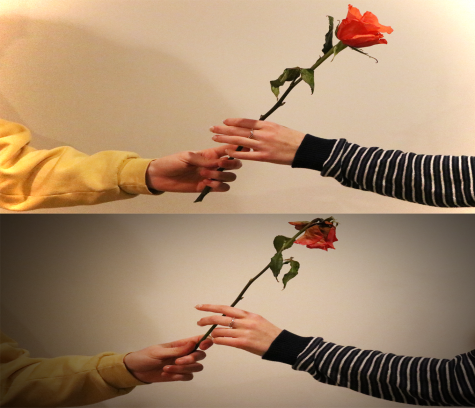

Michael accesses the records of two people’s lives measured in point values and compares two identical actions—selflessly cheering someone up by giving them roses—from two different time periods. Seeing that a man in the year 1543 received 143 points while a man in 2004 was docked four, Michael concludes that it’s not the Bad Place hijacking the system at all, but rather the fact that as the world has become more complicated, industrialized and interconnected, every action, no matter how well-intentioned, drags with it a damning set of moral anchors. The 2004 man bought his grandma flowers, sure, but the cell phone he used to order the flowers was made in a sweatshop, the flowers he bought were grown with harmful pesticides, and the CEO of the flower business is morally corrupt. Bingo.

This dilemma has raised the following question: Given that the world has become increasingly complex and with each act

As our culture continuously modernizes, it becomes harder to be a good person in the 21st century. In this example pictured above, a flower is shown dead to represent the harmful pesticides that are being used in this century.

ion a person takes comes an array of consequences, Can you still be a good person in the 21st century?

Tackling this query begins with defining what a “good” person is, what they do and determining the motives for their actions. Most people can probably agree on what makes a person “good.” Good people are honest, reliable, kind, generous without expectation of repayment. But in reality, the requirements for a truly “good” person are more complicated than all that. The answer is multifaceted. A good person is someone whose behavioral and psychological profiles perfectly match up. Not only must the person show virtuous tendencies — the world’s hallmarks for “good,” such as honesty, compassion, kindness, generosity, temperance, fortitude, justice and the like — but the person must act upon these virtues consistently and for the right reasons. Someone “good” is, for example, honest not just in a courtroom under oath but at home, at work, and while telling their friend what they really think of their outfit.

Leading the life of a “good” person may sound easy in practice, however, that damning set of moral anchors easily catches up with one’s lifestyle. Take veganism for example— a seemingly morally superior diet that aims to eliminate the suffering of animals for human consumption. Certainly this couldn’t produce negative impacts! Well, due to recent spikes in the diet’s popularity, multiple countries have fallen short on the vegan staple of avocados and, in turn, the price of the fruit favorite has greatly inflated. Even a lifestyle thought to be environmentally conscious can adversely affect the lives of others. “There are so many unintended consequences to well-intentioned actions, it feels like a game you can’t win,” claims a Good Place character, summing up this moral dilemma.

So if every action one takes, no matter the intention, results in negative consequences, then why even try to be a “good” person at all? The answer: for the starfish. “The Star Thrower” by Loren Eiseley describes the narrator coming across a man on the beach picking up starfish and throwing them back into the sea. He explains that if the starfish are not thrown back into the ocean, they will die as the tide retreats. The narrator questions his logic, explaining to him that there are miles of shoreline and thousands of starfish and that he can’t possibly throw them all back before the tides change. The man is aware. He knows that he can’t save them all, but to the ones he can save, he has made all the difference.

Although this world grows increasingly more complex by the day and contains more starfish than could ever be thrown back to the ocean, we must try. Regardless of all that we cannot help, we must actively choose to put good into this world, reflect upon our past mistakes, and strive to be better for others, for ourselves and for the starfish.