Beyond the Basics of Black History

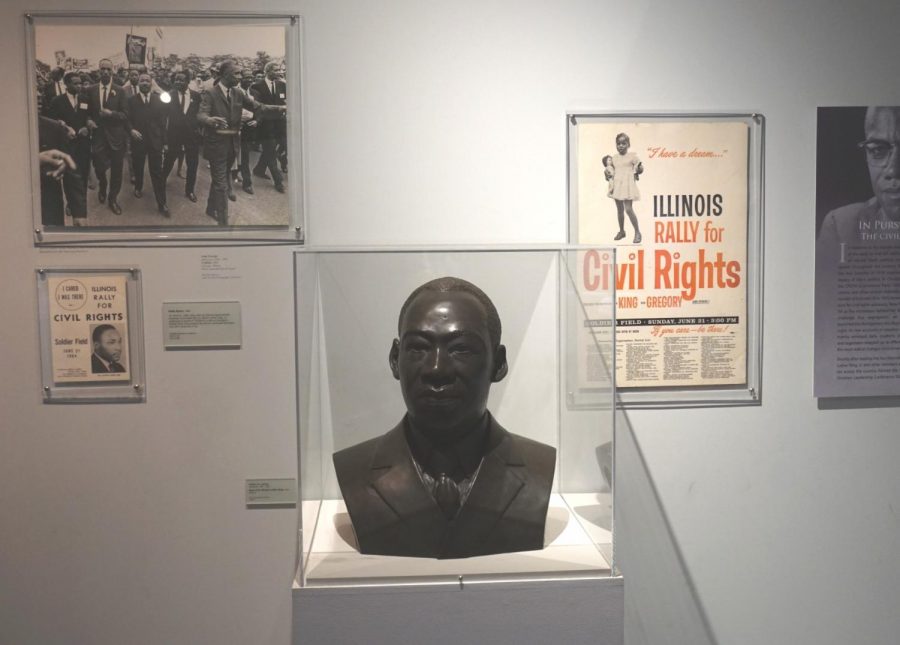

Martin Luther King Jr. was a prominent figure in the Civil Rights movement and inspired others even after his death in 1968. Martin Luther King Jr’s exhibit is located in the DuSable Museum of African American History.

The History of Black History

Feb. 1, 1865 marked a monumental time in United States history, especially for African Americans. On this day, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the 13th Amendment, abolishing the legal institution of slavery in the United States.

Fifty years later, in 1915, author, editor and historian Carter G. Woodson (known as the “Father of Black History”) began advocating for the creation of Negro History Week, which carried the message that “Blacks should be proud of their heritage and that other Americans should also understand it,” explains the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Lincoln and Frederick Douglass were each influential in promoting racial equality in the United States; both have birthdays that fall in February, the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) explained. These days have been celebrated by the African American community before February was even deemed Black History Month; Woodson thought that celebrations should be redirected from their focus on the individual men to recognition of the achievements of the race as a whole.

The NAACP explains that Woodson pushed for the creation of this celebration with certain morals in mind: “learning to accept insult, to compromise on principle, to mislead your fellow man, or to betray your people, is to lose your soul.” These principles were shared by W.E.B. Du Bois, another African American activist who gave presentations at Black History Month celebrations and applauded Woodson’s work in coining the holiday.

Each year’s celebration is focused around a central theme or message. This year, the theme is “African Americans and the Vote,” according to The History Channel. This was chosen because 2020 is the 100-year anniversary of the 19th Amendment — which gave women the right to vote — and the 150-year anniversary of the 15th Amendment, which stated that it was illegal to deny suffrage to someone based on their race.

Harold Washington was elected as the first African American Mayor of Chicago. Washington’s exhibit is located in the DuSable Museum of African American History.

How Black History is Recognized at LHS

In past years at Libertyville High School, students and staff have recognized Diversity Week during February. Aside from this week, however, LHS has no traditions to recognize Black History Month. Mrs. Anne Singleton, an English teacher and newly appointed Equity Coordinator, has plans to change this for 2020, though.

She’s worked with the Principal’s Advisory Board to come up with a list of possible school-wide events to recognize black history. One event she has planned is a trivia contest in the library about prominent people in black history. This trivia will include facts about well-known activists as well as not-so-well-known influencers of various racially-charged movements.

In the classroom, recognition of Black History Month is on a class-by-class basis, so depending on the nature of the course, different classes offer different lessons about black history.

U.S. History teacher Mrs. Kristi Robertson explained how she and the other U.S. History teachers talk about it, stating that because African American history is such an integral part of American history, it is inevitably taught throughout the year, not just in February.

In Spanish classes, black history is recognized differently. Spanish teacher Mrs. Sarai Nieto has plans to recognize Black History Month in her Spanish III Honors classes: her classes will look specifically into influential members of the Afro-Latino community. In addition to studying Roberto Clemente and his influence, she plans to teach her students about “La Borinqueña.” This comic features an Afro-Latina superhero from Puerto Rico in her journey to help recovery efforts after Hurricane Katrina.

While certain teachers are covering black history in their classes, senior Drew Hopkins, who is white and the president of History Club, worries that since not all students take the same classes, not all students will have sufficient knowledge of black history. He said that it’s important for all classes to cover it in some capacity, emphasizing that the only reason he’s even aware that February is Black History Month is from his own research outside of school.

Mrs. Singleton recognizes this issue and hopes to initiate classroom conversations about black history: “As a white woman, it’s important for me to know the story of all people of color and to learn more about their experiences and learn more about [black history] beyond Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman and maybe Frederick Douglass,” Mrs. Singleton explained. She continued by describing that in her own personal experience learning about African American history as a student, she wasn’t taught much more than the basics. Mrs. Singleton hopes to initiate change in education surrounding black history for the current generation of students.

In the 1970s and 1980s, history textbooks began to include more about black history than they previously had, but in the beginning of this reform, it tended to be a superficial add-on. The textbook writers would add a paragraph toward the end of a chapter to describe the happenings of African Americans during this time period, Mrs. Robertson said.

She believes that the coverage of black history spread throughout her class’s curriculum is sufficient and doesn’t want to return to the ineffective ways of the past: “For me to have a lesson specifically in February about African American history…that would almost be going back to that 1970s, 1980s tacky, superficial [approach].”

Hopkins agrees that while black history should be especially emphasized in February, that shouldn’t be where its education ends: “It does seem almost sort of like a token or participation trophy that one month a year you get to learn about black history but then the other 11, we learn white people history,” Hopkins said.

Mrs. Nieto agrees that black history should be a topic that is covered throughout the year, not solely in February. The first step to building black history into her curriculum, she explained, is for her to learn it: “It’s our job as teachers to do the research to inform ourselves of what contributions have been made that we’re not aware of that we need to become aware of, so that we then translate that message to our students.”

Junior Breana Jordan mentioned that during February, teachers could begin each class with an anecdote or recognition of a prominent black historical figure related to the course’s focus. Before moving to Libertyville in the middle of fifth grade, Jordan lived in Dallas. This idea of recognizing different influencers of black history came from her school in Dallas; bringing it to LHS, she explained, could be as easy as sharing daily facts on the announcements.

As one of the few black students at LHS, Jordan often feels a pressure to blend in with those around her: “I’ve had to sometimes refrain from reacting to things that I hear in the hallway because there is the stereotype of being the angry black woman…being one of the only few black people, it’s like once you’re labeled, then it’s kind of like, I don’t want to mess it up for everybody, so I kind of dim my light a little bit.”

When considering LHS’s predominantly white demographics, there’s not one answer as to whether or not it should influence the way black history is taught. Hopkins, for one, thinks that it’s even more important to emphasize black history at LHS: In not being a member of the black community, “you don’t get that experience at home, you don’t get that in your surroundings, so you need school as the place to teach you about that,” he explained.

On the other hand, Jordan thinks that everyone should receive the same education: “History is history and people are people no matter what,” she said. To her, what’s important is that no one is left ignorant of such a large part of history.