U.S. history’s flawed narrative

A large amount of the U.S history curriculum is built around the textbooks used in class. However, the textbooks contain problematic ideas that help support a common narrative of U.S. history.

America was founded as a shining city on a hill. We worked hard and braved the rugged frontier to tame the vast, uninhabited wilderness to carve out a blessed land of freedom and opportunity. We brought economic prosperity to millions and propelled the glorious capitalist free markets to the rest of the world. We defeated Hitler and kept the communist ideology from spreading across the globe. Now we’re number one: the greatest economy and greatest superpower there ever was on the face of the Earth. We might have had some growing pains, some early misfires as we grew into a great nation, but the great and glorious history of America cannot be denied.

So goes the common narrative that students across the country are subjected to. I exaggerate, of course, but the truth is not so far removed. Students are taught the history of America in a way that either leaves out details crucial to the whole picture of our history or that hides some of the darker truths and controversies behind clouds of supposed objectiveness or reason.

But serious historians understand the institutional evil of America’s foundation, the unimaginable human cost of our westward expansion and the subjugation of the third world that was vital to America’s economic success. They understand America was not solely responsible for the defeat of Hitler, the much deeper intricacies of the Cold War and the toll America’s rise to the top has had on the world.

Unfortunately, as much as we wish it could be, history isn’t a set of unchanging, irrefutable facts to be learned and memorized. History, by its very nature, is a narrative that changes its tune depending on who’s singing. What textbooks choose to include and how they choose to present that information is very important because they are framed as absolute fact. Many students never take another U.S. history class, and so what they learn in high school becomes their only interaction with the narrative. Therefore, U.S. history is one of the most important topics covered in a student’s academic career. It sets the groundwork for how we view society and helps provide context and a basis for critical reasoning when confronting modern issues facing our nation. This gives U.S. history textbooks and classes one of the most important responsibilities in the development of American youth. Across the country, they fail. Miserably.

Textbooks create an archetypal myth of American history so powerful that even when teachers try their best to tell the truth, it’s futile. The unfiltered facts don’t fit the overall story of the class and are thus rejected by students. We cannot process history in a vacuum, only in narrative: the true form of history. The narrative is all that is remembered and the narrative paints America with broad white strokes.

Sometimes, textbooks actively promote distasteful or harmful ideas or concepts in an effort to teach our history from the perceived “both sides.” One textbook used at LHS falls victim to this, too. The textbook used by AP U.S. History classes, written by Alan Brinkley, is filled with questionable phrasing and problematic ideas.

One of the worst examples of this in the Brinkley textbook is how it deals with the Klu Klux Klan in the post-World War I era. The book says “…where Klan leaders came from the most ‘respectable’ segments of society, the organization operated much like a fraternal society, engaging in nothing more dangerous than occasional political pronouncements.” The textbook goes on to say that the Klan “tried to present themselves as patriots and community leaders.”

Although the textbook briefly covers the violence the Klan wrought on minorities, there is an important truth that the textbook fails to cover entirely. The 1920s Klan acted as a political machine that wrested control of state positions from east to west. According to PBS’s The American Experience, entire states, such as Colorado or Indiana, fell under Klan control. This was known as the “Invisible Empire,” and its effect was felt from coast to coast. It gave the Klan a powerful hand in shaping both our nation and it’s narrative.

The inability of the textbook to flatly teach the truth–that the Klan was one of the evilest and most violent manifestations of the ever-present racism in our history–helps explain the misconceptions about America today. How can we understand what’s going on in our country right now if we don’t have an honest, accurate and helpful historical context for it?

California and Texas, as the largest states in terms of population, have a tremendous influence on the narratives in textbooks. According to The New York Times, publishers frame their textbooks around those two states, and it can have big impacts on the nation. These two states, generally speaking, have vastly different views on politics. This means that two vastly different narratives are sold. Regardless of the ideological bent of the book, allowing companies to sell books based on the world views of unelected state agencies is dangerous.

Another great failure of how U.S. history is taught is a failure to develop conversations and questions about the truth. Students are given a list of terms and names and told to memorize them. Alexander Hamilton, John C. Calhoun, John J. Pershing, J.P. Morgan, Robert McNamara. After the test, these snippets of information are forgotten, and nothing is truly learned.

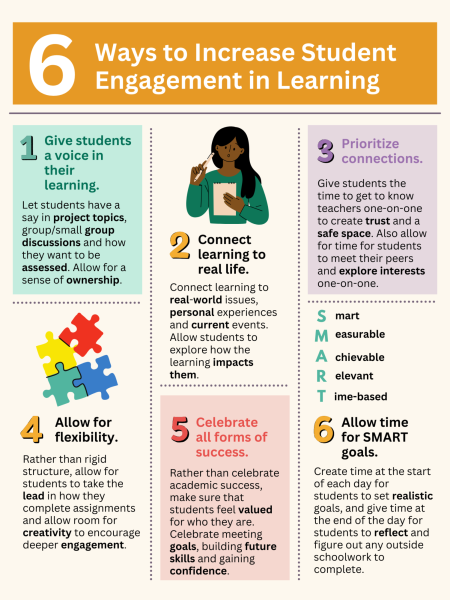

Suppose, instead, history was taught as a larger picture. More would be learned, as individual facts are seen in the context of the entire narrative. Questions should be asked, and issues should be dealt with. Instead of avoiding the controversy, classes should lean into it, examine it. Understand what effects these events had and discuss them. There should be less memorizing of disconnected information and more discussion of complex issues and their impact on history and how they shape the world we live in. Students should be encouraged to disagree with ideas presented and intellectual honesty should be promoted.

The problems with U.S. history, of course, are deeper than the way we teach it. As a society, we need to come to grips with the dark realities of our history, but teaching the truth and changing the way we teach our history will help us move forward in a more honest and helpful way.

Note: This column discusses the way many history classes are taught nationally and some of the issues regarding the broader narrative of America’s history. This piece is not intended to be about any classes at LHS or the LHS curriculum. Furthermore, suggestions or ideas presented in the piece are not meant to imply that staff members at LHS are not already doing so.

Nikolaus • Aug 15, 2024 at 1:10 pm

United states book American history book