Divisiveness in American Politics is Nothing New

Politics is constantly changing and adapting in order to adjust to the modern world. However, its fundamental aspects have remained the same from the time the United States was founded nearly 250 years ago to today. For one, the party system has remained a defining factor of American politics.

But as integral to the government as political parties may seem, a two-party system is mentioned nowhere in the Constitution, and George Washington even warned against their creation in his renowned farewell address.

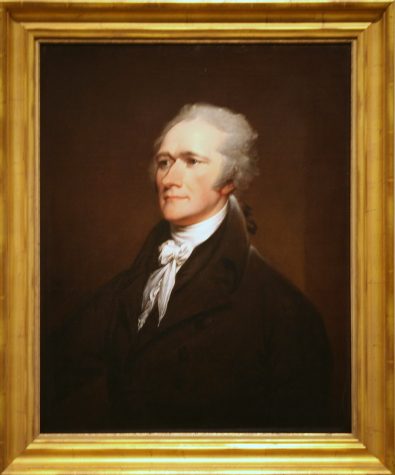

Why, then, do political parties in the U.S. hold so much weight in the political process? According to the Library of Congress, the answer extends all the way back to the late 18th century during the struggle to ratify the Constitution. The nation’s first party system was made up of Federalists, fighting for a strong centralized government, and Democratic-Republicans (also known as Anti-Federalists), who advocated for states’ rights.

This unintentional formation of two distinct groups fighting to define the government and, consequently, the future of the nation, set the precedent for politics today. The parties themselves have changed a number of times since this norm was first adopted in the late 1770s, yet its structure has remained a consistent and influential part of American politics.

The first major change in the U.S. party system was the dissolution of the Federalist Party, leaving the Democratic-Republican Party as the only viable option for voters. Gradually, the existence of only one major party created a divide among voters. After President John Quincy Adams lost reelection in 1828 to Andrew Jackson, the party split: Adams became a prominent leader of the Whigs, or the National Republican Party, while Jackson’s party became known as the Democrats, according to Britannica. President Quincy Adams was the last Democratic-Republican president.

Another major shift in political parties and alignment occured in the late 1920s through the early 1930s, with the realignment of southern Black voters from the Republican Party to the Democratic Party. The southern Democratic Party had historically suppressed the rights of African-Americans, thus becoming an unattractive option for Black voters. As the Great Depression disproportionately harmed Black communities, Republican President Herbert Hoover failed to implement economic reform to support those communities. Yet this demographic continued to support the Republican Party rather than realigning with the Democrats, according to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Mississippi representative John R. Lynch, a Black Republican, explained this phenomenon in the mid-1930s: “The colored voters cannot help but feel that in voting the Democratic ticket in national elections they will be voting to give their indorsement [sic] and their approval to every wrong of which they are victims, every right of which they are deprived, and every injustice of which they suffer.”

Elected in 1932, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a Democrat, then implemented the New Deal, which offered economic relief from the depression to Black communities and many others throughout the country. This relief, while minimal, as well as the Republicans’ refusal to pursue civil rights legislation, alienated Black voters, who then began to shift to the more progressive Democratic Party.

An already divided nation was split even deeper after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, according to the Heterodox Academy, a non-profit advocacy group. This act prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin, making it the most progressive civil rights legislation since the end of the Reconstruction Era (post-Civil War). The voter trends following the passing of this act have shaped the parties today; many white Democrats joined the more conservative Republican Party, while minorities tended to flock to the more liberal Democratic Party. These two parties were — and continue to be — dominant over American politics.

AP Government teacher Matthew Wahl credits the existence of this distinct two-party system to the winner-take-all voting system present in the U.S. In this system, a single party or group (i.e. Democrats or Republicans) can choose every elected official if they gain a majority of votes — no matter the margin between the winner and the runner up. This winner-take-all approach enables large, powerful parties while smaller and weaker ones are put at a disadvantage; Mr. Wahl attributes the lack of traction gained by small, third-party groups, such as the Green Party, to this voting system.

Naturally, a system with only two widely accepted options for voters to choose between enables conflict and divisiveness — not only conflict in policy but it can turn into conflict as a threat to basic decency.

Today, the polarization between the two sides is strengthened by the pervasiveness of social media and the accessibility of the news: “[Social media] just kind of puts people into their camps and really creates this divide,” Mr. Wahl said.

But the hostility in today’s political climate is nothing new, Mr. Wahl explained. Nastiness in politics dates back two centuries to some of the earliest presidential campaigns; for example, during Andrew Jackson’s campaign in the 1820s, the opposing party ridiculed his late wife as a political tactic.

Mr. Wahl compared this sort of personal attack to the ones seen today. He’s noticed that today, politicians and voters aren’t quite as forthright about the dirty tactics they’re using, but these tactics are certainly still being taken advantage of.

While it’s unlikely a politician would be ridiculed for being a widower in the 21st century, it’s certainly common to see a tweet making fun of a politician’s physical appearance — be it their weight, their hairstyle or their outfit.

With the tension and divisiveness caused by the two-party system, one might wonder what benefit this system serves and how it has lasted nearly 250 years. A commission report from 1986 by the Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations on the transformation of American politics credits the two-party system’s ability to turn ideas into legislation as an explanation for its continued existence: “No republic can flourish without enduring political instrumentalities which transform the public’s wishes into governmental actions, and despite shortcomings, American political parties have historically fulfilled this vital function.”