The Original Influencers

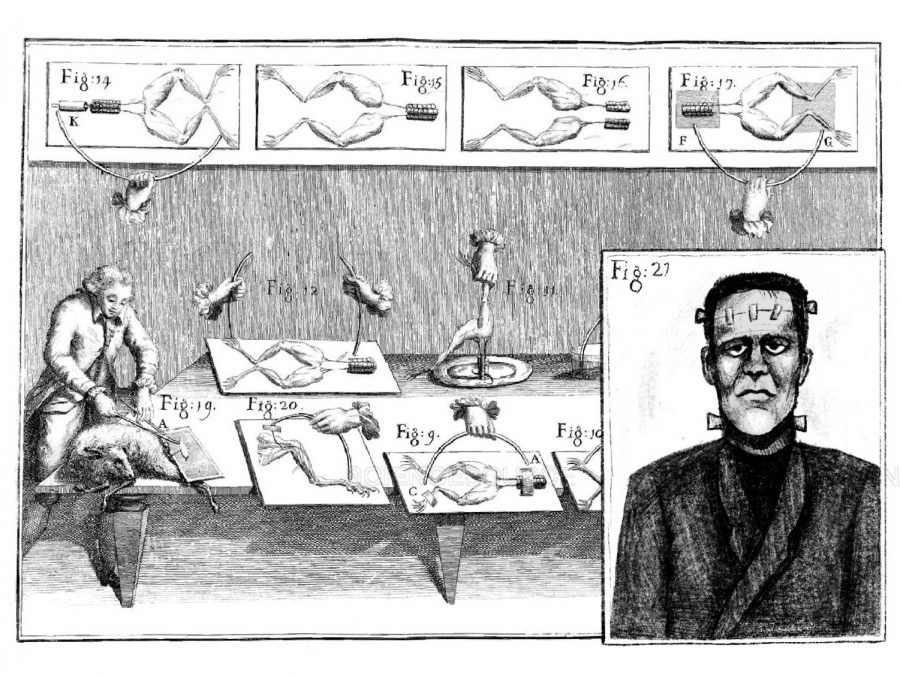

Frankenstein drawing by Paige Vang; background drawing from Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 4.0)

The well-known story of Frankenstein was deeply influenced by the science experiments in the early 1800s that tested muscle movements from electricity. The background image above depicts Luigi Galvani’s frog muscle experiment and its similarity to Frankenstein’s creation.

Was it mere coincidence that Mary Shelley published “Frankenstein” in the midst of the Enlightenment? Or was this fictional tale of science gone wrong shaped by the very real changes unfolding across Europe in the 18th century?

Far from being completely original worlds untouched by reality, the narratives that authors and screenwriters create are highly influenced by the cultures they are surrounded by, giving books and films an added layer of relevance.

For example, Shelley’s warning against the dangers of unrestrained scientific progress in “Frankenstein” was written in response to an age that heralded reason and experimentation as humanity’s savior.

Vox reports that the growth of magical realism in Latin America in the 1940s was a reaction against colonialism. In fact, its blending of two seemingly opposed concepts — realism and the supernatural — is considered by some to be an assertion of cultural relativism and the subjectivity of truth.

In an interview, English teacher Dyan Naslund emphasized the influence of political upheaval on writing, suggesting that the focus of “The Crucible,” written during the Cold War, on “witch hunts […] and people being persecuted for being different” was a result of the Red Scare.

The influence of reality on fiction isn’t limited to the past, either. According to the Foundation for Economic Education, the recent surge in the popularity of superhero movies can be linked to the economic recession of 2008. Periods of economic struggle often lead people to “look to superheroes as beacons of selflessness in an age perceived as corrupt and full of negativity.”

In contrast, English Department Supervisor Paul Reiff believes that the emergence of more morally complex villains a la “Game of Thrones” is a product of globalization and “postmodern thinking that truth isn’t even reality. […] It’s more a product of our own creation.”

Studies, such as the one conducted by Dr. Martha M. Lauzen — executive director of the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film — have revealed the impact that the double standard in our society in regards to appearance and gender has had on the film industry. Lauzen found that women appeared in “sexy attire” nearly four times as much as men in a pool of 1,200 popular films, mirroring the frequent objectification of women in real life as well.

The exchange between culture and media isn’t one sided, either. According to Nancy Wang Yuen, a prominent sociologist who studies the impact of stereotypes in television, “researchers have found that prolonged television exposure predicts a decrease in self-esteem for all girls and for Black boys but an increase in self-esteem for white boys” because Hollywood often “casts white men as heroes, while erasing or subordinating other groups as villains, sidekicks or sexual objects.”

Furthermore, a paper from the University of Austin by Charles Ramirez-Berg found that for those not part of marginalized groups, the prevalence of stereotypes in film and literature can lead to many believing that instead of being wildly inaccurate and offensive caricatures, these portrayals are actually reflective of the lives of real people.

Research like this is part of the reason why the call for good representation and diversity in media has grown so strong. According to Dr. Reiff, “We tend to read a lot of works that are [from] white male authors from the 1900s or 1800s, and I think we need to blow that apart and introduce books, not just about women or people of color, but written by women and people of color.”

When works of literature or cinema are written responsibly, they can have profound positive effects on the perspective of the public. Aside from giving students a better understanding of their own world, a study by psychology professor Keith Oatley found that when compared to a group of non-readers, those who did read fiction performed higher on tests of empathy. An article published in Discover Magazine postulates that this is because “fiction has the capacity to transport you into another character’s mind, allowing you to see and feel what they do.”

Ms. Naslund added onto this idea, stating that when she teaches about Daisy Buchanan in “The Great Gatsby,” “There are so many reasons why students would hate this character, but then when we start to look at her psychology, and we start to look at her past, and we start to kind of think about why might she be acting that way, I think what we try to do is open the door to empathy.”

When creating a reading list, librarians Amy Wiggins and Melissa Aubin recommend finding a balance between books that reflect one’s own experiences, “mirrors,” and those that can help one understand the perspectives of others, “windows.”

Additionally, Ms. Naslund encouraged students to seek out teachers for advice on what to read next and stressed that “reading about other experiences […] is so valuable because we can’t possibly have every experience under the sun, so we really should try to read about them if we can.”