Settling in the U.S.

Life as an Immigrant in Libertyville

“The land flourished,” President Lyndon B. Johnson declared at the signing of the Immigration Act of 1965, “because it was fed from so many sources — because it was nourished by so many cultures and traditions and peoples.”

The history of the United States is steeped in a tradition of immigration, whether that be its role in cultivating the country’s diversity or acting as a target of dissent. In 2019, more than 460,000 U.S. immigrant visas were issued, according to the U.S. Department of State, and slightly more than one million additional people obtained lawful permanent resident status, per a report by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. An average of nearly 510,000 individuals have entered the U.S. on immigrant visas over the past 10 years, and some have made a new home in Libertyville.

Senior Cristina Tuduri Poza immigrated to the United States from Spain following a job offer for her father. Since the move before her freshman year, Tuduri Poza’s family has been devoted to keeping their Spanish culture alive.

“We speak Spanish at home; my parents cook Spanish meals and make sure that we keep in touch with everyone back in Spain,” Tuduri Poza shared.

While many of her relatives are thousands of miles away, a group of local Spanish families has served as her “family in the U.S.,” getting together and sharing meals.

Junior Rofaida Abdel Rahman, who immigrated to the U.S. from Canada in August 2019, shared similar sentiments.

Originally from Egypt and having moved as her father advanced his education and career, her parents have encouraged her to maintain the culture of those roots: “My parents made sure…that I went to Arabic school, [they] always talk to us in Arabic…[they] love it when I try to spread as much of our Egyptian culture as [I] can.”

Abdel Rahman also noted the impact Canadian culture has had on her interactions with people. While she has found that people don’t often create conversations with strangers here, in Canada she learned the value of being “kind to everybody and always smiling, always creating conversation.”

Moving to a new country and acclimating to a new culture proves to have its challenges as well.

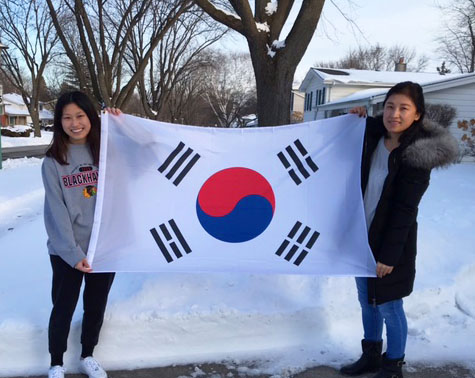

Junior Yelim Na emigrated from South Korea when she was 9 years old after her father’s job was relocated and recalled how little she knew of the United States at the time of her move.

“I had never thought about moving to a different country before moving,” she shared. “My parents tried to help me…they bought books for me about American history and made me read [them], but it didn’t really help because they only talked about history and not the culture and the people.”

Tuduri Poza explained that while being bicultural may sound exciting to some, it can be difficult to establish an identity: “I don’t fit in anywhere; when I go to Spain, I’m the American and when I’m here, I’m the [Spaniard].”

“It’s like I have two different parts of me…I realized that my Spanish self is definitely different than my American self,” she remarked.

Abdel Rahman also detailed struggles with her identity. She described the diversity and celebration during the parades of Cultural Week in Egypt with large flags, and “everyone on each others’ shoulders…playing their music and dancing.”

“As much as I love my culture and love representing who I am and where I come from, I realized that I wouldn’t be able to spread that joy and stuff because most of the people here…they’re only American,” she said.

Junior Harry Johnson, who emigrated from England around the age of 8 for his mother’s work, remembered the shift to U.S. suburban living as difficult to adjust to.

“In England, everything’s much closer together, and there’s a lot more walking,” he shared. “You can get everything you need within a 10-minute walk radius of your home, and then when it becomes a 10-minute drive radius of your home [in the U.S.], it’s very weird.”

One of the greatest obstacles to immigration can be permission to enter the country and access to different opportunities once permitted entry. Obtaining visas and green cards can take months or even years to apply for and process, without the guarantee of approval by the U.S. government.

Tuduri Poza recounted the difficulty her family faced in getting back into the U.S. after a trip to Spain. “We had to ask the United States Embassy in Spain, and we had problems with that,” she said. “It’s harder to go and come back if you don’t have citizenship.”

Abdel Rahman, Na and Tuduri Poza found that adapting to differences in language and slang takes time.

“I have to stop writing color with a ‘u’,” Abdel Rahman shared, in reference to the Canadian spelling of words. “Trust me…that’s so much harder than anything because every single time, I’d write ‘favourite’ or ‘colour’ or ‘labour.’”

She grew up speaking English and Arabic and was immersed in some French while living in Canada. Though the punctuation and letters of Arabic are different than French, Abdel Rahman found that speaking Arabic made learning French, and later Spanish for a few years, much easier.

Na began learning English while living in South Korea due to its requirement in school and additional tutoring classes. Though she had this background upon immigrating to the U.S., she remembered adapting to the language difference as being “really hard at first.”

“When I was learning [English], people would stay stuff slowly because we were learning it, but then [in the U.S.], people talked faster than I was used to,” she remarked.

Tuduri Poza was also exposed to multiple languages from a young age. In addition to growing up speaking Spanish, she took extra English classes and participated in five English exchange programs.

Coming to the U.S., she did not find language to be much of an issue but struggled in classes with specialized vocabulary, such as math. She continues to embrace the learning process of language and is consistently surprised by novel words and expressions.

“I can probably learn a new word every week or so,” she shared. “Sometimes I surprise myself and I’m like, ‘How did you go through years not knowing this was a thing?’”

According to U.S. Census Bureau data from 2015-2019, 10.8% of Libertyville’s population was born in a foreign country. Though settling into the atmosphere of a new country and community can be daunting, these students have found comforts and guidance throughout the process.

Aided by friends he made upon his arrival and immersed in holiday traditions that paralleled those in England, Johnson counts himself lucky to have moved to the U.S. when he did.

“As an immigrant, I think we came at one of the best times to be an immigrant from England to America,” he remarked. “We [had] enough money to live here and Brexit [hadn’t happened] yet.”

Similarly, Na pointed out the support she received from the friends she made as she settled in the U.S.: “Even though I didn’t really know them very well, they invited me…and then they introduced me to their friends.”

Abdel Rahman has appreciated the competitive nature of LHS’s academics and also expressed gratitude for the dedication of teachers: “One of the biggest things that really blew my mind is [that] teachers love to teach here…[They] put so much effort into their classes and stay after school for hours and come to school early just to be with kids.”