It’s Time to Focus on the Little Picture

I was in ninth grade when I began to notice the term “police brutality” cropping up more and more in news broadcasts and casual conversations. While, initially, the right stance seemed abundantly clear to me, the conflicting comments and accounts I quickly encountered left me scrambling for the truth in a constantly shifting maze. Overwhelmed, I turned to the one place that had never failed to give me honest answers: the library.

When I picked “Dear Martin” off the shelf, I was searching for a sense of clarity and a perspective that had been strangely absent in all the discussions I had overheard, but I hadn’t expected that the book would affect me on the deep emotional level that it did.

The coverage of police brutality I had previously been exposed to rarely bothered to tell the full stories behind the names in their headlines; any background given on a victim was usually an attempt to justify the indefensible.

“Dear Martin” marked a stark departure from this trend. I watched from a distance as Justyce McAllister, the novel’s teenage protagonist, prepared for debate tournaments and math exams while dealing with microaggressions from his peers. I watched as he began to fall in love with his middle-school crush while still reeling from the death of his best friend at the hands of the people sworn to protect him. I watched as his unflinchingly honest journal entries to Martin Luther King Jr. brought an issue that had once felt distant to me much closer to home.

Here was a collection of words that, in focusing on the unique experiences and thoughts of a single person, had managed to lead me out of that twisting maze and to a place of unwavering conviction.

While cold statistics and impersonal generalizations are most frequently used to raise awareness about an issue, there is no doubt in my mind that the story of Justyce strengthened my belief in the exigency for the protests breaking out across the country in a way those other strategies could not.

With our country in the throes of increasing polarization, it’s become evident that traditional methods of exposing each other to important social and political struggles haven’t been capable of fostering the culture of compassion our country so desperately needs right now.

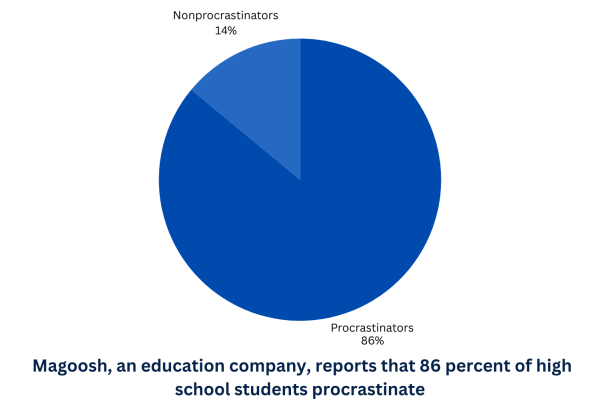

Yet, we continue to rely on complex charts and distant data points to prove our points, the need for our audience to see the “big picture” often leading to a grand dismissal of any sort of individual stories.

However, the use of these individual stories may be the key to truly generating empathy for the perspectives of others and the causes they are fighting for.

After all, some of our generation’s greatest movements have been kickstarted by the dissemination of a single person’s story to the public .

While the personal narrative has long been maligned as an ineffective and irrelevant form of evidence, its staunchest critics should consider the fact that a large body of their favored statistical evidence suggests the contrary.

As explained by humanities professor Hans Hoeken of the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands, anecdotal evidence has historically been found to be more persuasive than statistical evidence because of its “higher imaginability” and “vivid” nature.

In fact, a study from Dr. Onome Ogueh — the chief medical director of Delta State University Teaching Hospital — compared how story based lessons versus traditional fact-based lessons impacted the ability of a group of medical students to learn new content. He discovered that “the stories generated a lot of emotion in the learners, emotions that deepened their understanding of the topic covered.”

More importantly, personal narratives are able to highlight the deep implications of a certain disparity or problem while avoiding dangerous blanket statements.

Too often, the attempt to reveal both the scale and gravity of an issue through traditional methods can result in a vague simplification of the matter or a homogenization of the experiences of a diverse group of people.

This can be especially problematic because such generalizations could cause the audience to develop blindspots where they believe that a certain injustice only manifests in one particular way.

James Baldwin once said, “I am what time, circumstance, history, have made me, certainly, but I am also much more than that. So are we all.”

And perhaps that is the true beauty of the personal narrative. It can boldly reveal the way a life is molded by outside forces, whether they be benevolent or cruel, but it never strips the individual of their agency, never reduces them to only one aspect of their identity. The author makes sure of that.

It is this ability of stories to display the entirety of an individual that could make them so effective in creating a world where empathy is the norm.

It is much more difficult to dismiss the need for change when you become deeply acquainted with an individual and learn how your inaction might be actively harming them as opposed to when you’re merely scrolling through reams of faceless data.

I am by no means suggesting that we should throw facts and statistics to the wind nor that we should shift the responsibility of eliminating ignorance about global issues to those who have been most affected by them.

However, in order to create a more understanding and tolerant world, traditional evidence can be fused with the “little pictures” that libraries and art galleries across the nation are bursting with.