Disparities Across Districts: How Illinois school funding causes inequities in learning

North Chicago is only around a 25-minute drive from Libertyville, yet the two towns experience dramatically different situations when it comes to school funding. According to Advance Illinois, an education policy and advocacy organization, District 128 is funded to 171% of adequacy but North Chicago’s SD 187 only receives 54% of adequate funding.

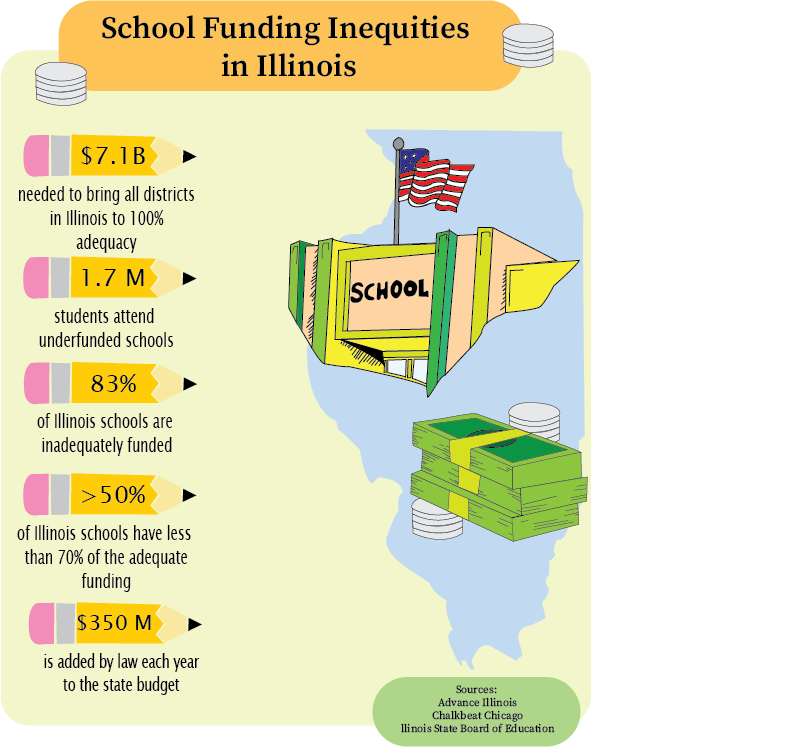

This type of inequality is not unique between North Chicago and Libertyville. In fact, Illinois’s school districts face some of the most unequal funding in the nation, according to a 2018 report by Education Trust, a Washington D.C.-based education advocacy group. In Illinois, over 83% of school districts are inadequately funded and over 50% of schools receive 70% or less of adequate funding. More than 1.7 million students attend these underfunded schools.

The Causes of Inequitable Schooling

The main reason for these school funding gaps has to do with how Illinois funds education. According to John Price, superintendent of North Chicago SD 187, “we primarily rely upon property taxes to fund schools, and our state constitution is interpreted to mean that the state does not have an obligation to pay a majority of funding for schools.”

In fact, local resources — primarily property taxes — provide the majority of funding for school districts, usually around two-thirds of overall funding, with state and federal funding comprising the rest. This means that schools in areas with lower concentrations of wealth receive less funding from property taxes. Conversely, areas with relatively higher concentrations of wealth receive significantly more funds from property taxes, despite residents of these cities usually paying a lower percentage of property taxes. According to Dr. Price, because North Chicago property values are relatively low and still haven’t fully recovered from the 2006 housing crash, the city needs to have a higher tax to generate the same amount of revenue as a wealthier city with a lower percent tax on property.

According to LHS equity coordinator Anne Singleton, racist housing policies contributed to creating areas of concentrated poverty.

“Throughout the 20th century, certain neighborhoods were redlined, as in these are neighborhoods where Black Americans can live and other neighborhoods were color-coded differently for white Americans,” Mrs. Singleton said. “Redlining then caused homes in certain areas to be worth less money, because that’s where Black families lived. Housing segregation is often pointed to as a reason why schools are unequal, because the houses in a neighborhood are what, in large part, determine property taxes, and then how much money a school gets.”

Mrs. Singleton explained that one of the reasons that these inequities have persisted is the perception of what it would take to fix them.

“One of the big reasons it doesn’t change is because people don’t want to give up what they have. And oftentimes, that’s what people believe would have to happen in order for schools to be equitably funded. I don’t think that necessarily is the case. I don’t think it has to be that way. But I think that’s how it’s perceived,” she said.

According to State Senator Dan McConchie (R), who represents the 26th State Senate district which includes Libertyville, the political reality of structural changes in education makes it hard for members of state congress to vote for them.

“Let’s take a state representative or state senator who’s representing an area along the North Shore. Do you expect that person to then vote against what their constituents want them to, by essentially making the argument that it’s for the betterment of kids elsewhere?” he said. “It’s just a very hard thing to do for elected officials who are supposed to be representing their constituents, while also looking out for the state as a whole.”

The Evidenced-Based Funding Formula

Recently, progress has been made in combating statewide schooling inequities. In 2018, the state implemented its new Evidence-Based Funding formula, which McConchie described as a good compromise.

According to Advance Illinois, the formula gives each school district an adequacy target, indicating the amount of funding needed to provide a quality education. Each district’s adequacy target is unique and based on factors like size, number of low-income students, and the amount of English language learners in a district. The formula increases the state budget for school funding by $350 million each year, with a goal of reaching 90% adequacy in all districts by the year 2027. This number falls short of the Illinois State Board of Education (ISBE) analysis that indicates that, in order to reach that goal, the formula would need to increase funding by $660 million each year.

Rep. Rita Mayfield, a Democrat from Waukegan, expressed concerns about the amount of money being put into the formula.

“Is $350 [million] enough money? I’ll tell you honestly, no, because even at putting $350 million into this equity funding model, it’s still going to take 30 years for our poorest performing schools to reach equity,” she said

The formula does not affect the funding a school receives from local property taxes, but directs state funds to schools that need it the most. For example, North Chicago SD 187 — where 26% of students are English language learners, 84% are low-income and 94% of students are people of color — receives $176 per pupil under the Evidence-Based Funding formula.

On the other hand, D128 — a district where 1% of students are English language learners, 10% are low-income and 27% of students are people of color — receives $1 per pupil, according to Advance Illinois.

Dr. Price said that when the formula was implemented in 2018, he started to see progress.

“When I arrived in the district in 2017, we had two music teachers in the district. So that’s one thing that we’ve done with our evidence-based funding models, is now we have a music program in every school. That was a big deal,” Dr. Price said.

Dr. Price doesn’t see the formula as a perfect solution to the issue but instead as a big step in the right direction.

“I guess it falls short of a solution, but without dramatically changing the way that we tax and fund school systems, it does address the issues,” he said. “Given enough money and time, we’ll address the biggest problem.”

However, the Evidence-Based Funding formula ran into a wall with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic. No new money was added to the formula in 2020, much to the chagrin of advocates of the formula. Mayfield expressed her disappointment that the formula went unfunded.

“Our children’s education should be tantamount. That should be at the forefront of everything. We have to make sure that we are providing a quality education,” she said

The governor’s budget was contrary to the ISBE recommendation that the state increase the education budget by $412 million due to the loss of learning from the coronavirus pandemic and the unequal experience in online learning between districts.

Mrs. Singleton commented that the coronavirus pandemic has illustrated the problems with school funding.

“What [the pandemic has] done is put a magnifying glass on those gaps. Covid has pulled back all the layers and showed us this is how inequitable schools are,” said Mrs. Singleton.

Dr. Price noticed the extreme differences when the pandemic broke out and schools shut down too.

“You know, when Covid started back in March, a lot of my colleagues were like, ‘What are we going to do about the kids traveling to France?’ ‘Oh my gosh, what am I going to do about the kids who are on their way to Japan?’” he said. “[That’s] not a problem I have … I’m trying to get food to families’ homes and keep people fed and other districts are worried about kids that are overseas right now and how do I get them home.”

Despite the problems the pandemic has posed, McConchie is certain that once the state weathers the crisis, the formula will move ahead as normal.

“I fully expect that once we are able to get to a point that there is money available, that [the formula] is top of the list of priorities,” he said.

District Consolidation and Sales Tax

Another method of working to make school funding more equitable that has gained support on both sides of the aisle is district consolidation. Illinois has 852 school districts, the third-highest number in the nation, according to the University of Illinois’ WILL Illinois Public Media. Senator McConchie used the District 128 area as an example of district consolidation. Currently, Rondout School District, Highland Middle School(District 70), Oak Grove School District and Hawthorn School District feed into D128. Each one of these districts has their own administration, whose salary is relatively high compared to other salaries in the education sector.

“The idea would be to merge these districts, and then you have a leaner, more efficient administration that is still doing the administrating, even though it’s over more kids and more programs. So I do think that school district consolidation is important,” said McConchie.

Illinois House Representative Chris Bos (R), who represents the State 51st House district, which includes Libertyville, also suggested district consolidation as an effective strategy.

“The number of administrators that are making over $100,000 a year is vast. And so, remove some of that [and] put that funding back into the schools, instead of the administration,” he said.

Recently, Mayfield sponsored a bipartisan school consolidation bill in the Illinois House of Representatives, which Bos co-sponsored. If passed, House Bill 7 would create the School District Efficiency commission, which would look into where money can be saved by consolidating districts. The bill aims to reduce the number of school districts in Illinois by at least 25%. Supporters of the bill say that it could save $700 million by reducing administrative spending.

“It doesn’t force consolidation, it doesn’t close down any schools, doesn’t require the termination of any person within any school building,” Mayfield explained. “It simply creates a commission to look at all of the school districts across the state of Illinois to look for where it would make the most sense for a school district to consolidate.”

Mayfield mentioned that her bill has seen significant pushback from lobbyist groups representing the interests of superintendents.

“[Superintendents] have a really strong lobbying arm and have done everything in their power to shut down this bill, not because they’re trying to protect the students or they’re trying to protect the districts. They’re looking to protect their jobs,” Mayfield said.

Beyond consolidation, there are other ways of combating the issue. Dr. Price suggested that perhaps Illinois’ tax structure is inefficient in producing revenue for the state because the economy has shifted.

“We’ve got an incomplete tax base in Illinois because we don’t tax any services; we only tax goods and property,” Dr. Price said. “We don’t tend to have a tax when you go and get a haircut. And our economy has shifted. So the percentage of our economy that’s related to goods has decreased while the percentage of our economy that’s related to services has increased, and we don’t tax those economic activities. So, our tax base is no longer in line with our economy.”

According to the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability (CTBA), a bipartisan think tank that advocates for economic justice, the average number of service industries that are taxed through a state’s sales tax is 51. Illinois, on the other hand, taxes only five. This disparity means that despite services making up 72% of Illinois’ economy, the majority of its sales tax focuses on goods, which only account for 17% of the economy. The CTBA estimates that $2.1 billion in revenue could be generated for the state by widening its sales tax base.

Although Bos agrees that the current system for school funding isn’t equitable, he’s skeptical about new or different taxes as a solution. He points out that it isn’t necessarily popular with the voters, who just last year rejected a proposed statewide graduated income tax that would have brought in $1.4 billion a year by increasing taxes on the state’s wealthier residents and lowering taxes on low-income residents.

“It’s a question of would [those taxes] create and incentivize business or would that hinder the growth of those businesses, where the businesses are paying other taxes, whether it’s income tax, or sales tax or any of the other business taxes that are on there,” Bos said.

However, the CTBA points out that widening the sales tax base might actually decrease the overall tax burden, allowing the state to lower the sales tax rate.

McConchie didn’t comment on the idea of a service tax, but he did articulate that the property tax system now is unfair because it isn’t dependent on the amount of money you make.

“We need to move away from that system of property tax. Property taxes are a very kind of regressive (a uniform rate that takes a proportionally greater amount from people with lower income) and not fair way to fund government, generally speaking,” McConchie said.

Inequitable Funding Causes Inequitable Learning

Regardless of how the issue is solved, there is a general consensus that the old system isn’t working. The Evidence-Based Funding formula seems to have been a step in the right direction, but it’s not a total solution, especially with it being left unfunded for a year shortly after its implementation.

The effects of inequities in school funding are very real, however, and don’t take a break just because the Evidence-Based Funding formula does.

Mrs. Singleton described that even simple things like furniture can be affected by school funding. Less-wealthy districts might have to rely on donations from other districts or buy cheaper furniture for their students.

“So even just their physical comfort of being in [school] is impacted by funding,” she said.

Beyond physical comfort, the lack of funding has even more severe consequences on education attainment. According to a report from Learning Policy Institute, a nonpartisan education research and advocacy group, school districts with less funding tend to have lower educational achievement and graduation rates.

Conversely, better funding does more than just increase school statistics.

According to a study conducted by a team of experts from Princeton University, Columbia University and City University of New York, tracking U.S. Census data and the effects of schooling reforms, increased funding equity correlates with a decrease in crime, welfare, and incarceration, along with an increase in wages. In fact, the study found that in the long run, investment in education saves money due to decreased spending on public health, the criminal justice system and welfare systems.

According to Mrs. Singleton, this trend starts at a very young age. She explained that if a student hasn’t reached a certain reading level by third grade, it can be harder for them to make up the gap as they continue their education.

“They’re behind and so then that impacts their ability to be successful in middle school and high school, which then impacts beyond that,” she said.

Mrs. Singleton also believes that the effects of school funding on learning achievement impacts the way students view school as a whole too.

“I think it really eats away at their intellectual curiosity. School does not become a comfortable place; school is painful,” Mrs. Singleton explained. “They go in, and they’re being told repeatedly that they can’t do it, because of those materials that they’re given.”

But it’s important for students to feel comfortable at school, according to Mrs. Singleton.

“One of the things we discovered with this pandemic is how much schools play a role in students’ social-emotional well-being and in their physical well-being. Some kids, the only meals they would get would be breakfast and lunch at school. That was the food that they got for the week,” she said. “Some kids, as far as their identity, and how they see themselves, they may not be accepted at home, and at school, they are accepted for who they are.”

To Dr. Price, the inequity in Illinois is inescapable: “Our schools have less money to spend on our students but our students need more resources to be successful,” he said.

Beyond academics, a lot of enrichment activities that a student who attends a D128 school is offered are not accessible to North Chicago schools. Things like student newspapers, aquatic teams, marching bands, travel abroad programs and more aren’t offered at North Chicago, largely because of the inequitable funding system.

“Our students haven’t had some of the exposure and enrichment opportunities that students in wealthier districts have had,” said Dr. Price.

He also explained that the concentration of poverty in North Chicago affects students’ lives outside of school.

“Our park district is also underfunded. Our library is also underfunded. Those are all funded through property tax levies in our community, and so our head librarian and I have some of the same challenges,” Dr. Price said. “The head of the park district has some of the same challenges and so those cause reduced opportunities. Storytime and meet the author and golf clubs and swimming lessons and all of those things don’t exist.”

One thing that seems to be unaffected by the inequitable funding is North Chicago’s sense of community. Dr. Price spoke proudly about seeing the community come out to support the students: “Whether you get fireworks or not, the community is coming out to watch the kids play. And that’s really joyful, I mean, that’s just, it’s a great experience and vibe in the stadium and in the auditorium.”