Mental illnesses should not be the punchlines of our jokes

Warning: Story speaks of suicide and mental health illnesses.

“I have PTSD from that.”

“She’s been depressed lately.”

“I’m so OCD.”

“He’s bipolar.”

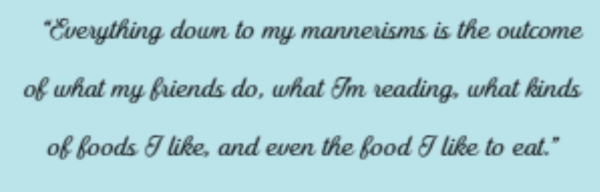

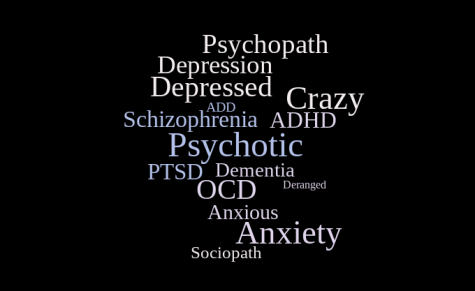

As the discussion around mental health and illnesses have become more prevalent in our lives, phrases and words like these have found their way into our language. Although it is seemingly positive that we have gotten more comfortable with open discourse surrounding mental health, our casual use of words that represent serious mental health problems is an issue. In fact, the stigma surrounding mental health persists and is perpetuated by this daily language that we use everyday with our friends.

According to the New York Times, last December, the US surgeon general warned of a “devastating” mental health crisis among adolescents. Also, emergency room visits by children and adolescents since 2019 rose sharply for anxiety, mood disorders and self-harm.

So mental illness is real. And a lot of us are affected by it, directly or indirectly. No one would ever joke about a debilitating chronic physical illness. Or if you sprained your ankle, it wouldn’t be socially appropriate to call yourself disabled. But using mental illnesses to describe people and emotions has become extremely common in our teen language.

For example, hearing passive mentions of suicide in casual conversations has become normal to senior Astrid Mazzeno.

“I’ve seen a lot of people say ‘Go kill yourself’ as an insult,” Mazzeno said. “I’ve also seen people say, ‘Oh, this makes me want to kill myself.’”

Obviously, it’s rare that people say these things maliciously. Most of the time, it’s meaningless. It’s just a word. It’s just a passing description of our feelings. It’s just a joke.

However, these phrases not only attach negative connotations to mental illnesses, but they also catalyze false awareness about what it’s like to actually be afflicted by the condition. For example, being bipolar is so much more than just feeling happy and then feeling mad a couple hours later. And for those who actually suffer from those afflictions, hearing their actual illness in jokes may feel dismissive, or may make it harder for them to get the help that they need. It can make it feel uncomfortable to share that aspect of their lives with others.

It does feel slightly counterintuitive that talking more casually about mental illness would actually strengthen, not reduce, the stigma surrounding it. But instead of being honest about it, we are making it more alienating and diminishing for those who seriously suffer from those conditions that are being reduced to mere offhand remarks.

I am not beyond fault. I have used phrases like these too. But being a teen with a mental illness myself, I have felt discomfort when people mention certain things so casually. I have laughed things off on the surface but felt more hesitant about being vulnerable around others with my problems.

So we should be more careful and deliberate about how we use this language. We can still express ourselves without using those specific words. Even if there isn’t a defined way to measure if it works, why shouldn’t we try? By no means do we have to change the way we banter and laugh with our friends; we can just be a little more mindful about how we refer to mental illnesses.

Maybe we can spare someone some discomfort. Maybe we can make it just that much easier for someone to accept their condition and get the help they need. Maybe we can make someone feel less alone.

According to a linguist in Psychology Today, our teenage years are when our linguistic preferences and patterns get set, and the new forms of language eventually become the norms for the wider community.

Just by making small changes to our vocabulary now, we will be taking steps to de-stigmatize mental illness for everyone in the future.