To vote or not to vote? That is the question, and the answer is clear: if you can vote, you should.

Voting is not just a civic duty; it’s a powerful tool that upholds the fabric of democracy (or representative republic, if you want to be specific, but the principle still holds). Democracy thrives on participation and voting – the exercising of our collective voice – is how we influence government decisions and accountability.

High voter turnout helps create a government that is more responsive to the people it serves and often correlates with more representative outcomes. For instance, the 2020 election, with increased turnout, led to the 117th Congress, the most racially diverse in history. Furthermore, the 2018 midterm elections, marked by high turnout, resulted in significant shifts in the House of Representatives to match the mostly democratic voters, demonstrating how participation can influence policy and political direction.

Conversely, low turnout can result in a government that caters to a narrow segment of the population, leading to policies that might not serve the majority.

To visualize this, imagine you’re on a bus with other passengers, and the driver asks for a show of hands to decide whether to (A) drive off a cliff, or (B) drive through an obnoxiously loud area. You face three choices: A, B, or abstain.

Not voting forfeits your chance to influence the decision, potentially enabling the most dangerous choice. If you abstain because you dislike both options, you let others decide, which can be disastrous if the majority chooses to drive off a cliff.

While this analogy simplifies (and exaggerates) the gravity and complexity of the voting process, the principle holds: inaction can lead to the worst outcome, making abstaining more harmful than choosing an imperfect but less harmful option.

Some may argue that the system is flawed, or they feel as if their vote doesn’t count; abstaining from voting can be seen as a powerful statement against a system that doesn’t represent one’s values. However, change often starts with collective action. Numerically, while it’s true that a single vote might not always sway an election, countless elections have been decided by small margins, proving that every vote does count.

Moreover, while the electoral college faces (valid) criticism due to its elite rather than participatory nature, many states have procedures in place that bind electors to the popular vote. Faithless electors are extremely rare; according to the national archives, In the 2016 election, only 7 (1.3%) of the 538 electors were faithless. Thus, while electors acting contrary to the popular vote exist, they’re a statistical anomaly.

While gerrymandering, state biases, and lobbyists can diminish the impact of individual votes nationally in a representative republic, high voter turnout in local and state elections is crucial for driving reforms like fairer redistricting, even in traditionally red and blue states. Voting empowers citizens to hold elected officials accountable and counteract lobbyists’ influence. High voter turnout compels candidates to address a wider range of concerns, including those often ignored by lobbyists.

For example, a 2019 study published in the American Economic Review found that increased voter turnout in local elections led to more equitable public spending and improved policy outcomes.

A common argument against voting is that no candidate perfectly represents one’s views, but abstaining isn’t effective. While “choosing the lesser of two evils” may be an electoral practicality, it’s not always black-and-white.

Voting is not necessarily choosing between two political parties or candidates, but vouching for the candidate that addresses your priorities.

Strategic voting influences governance by promoting incremental change. It encourages candidates to address public needs more effectively and enables participation in ballot initiatives and referendums that impact federal policies.

Websites like Ballotpedia and VoteSmart provide clear breakdowns of ballot issues, making the voting process and being an informed voter more accessible. It is one’s responsibility not only to vote, but to be an informed voter. Even if this lack of awareness is so widespread it’s problematic, abstaining from voting does not address the dilemma’s root cause; open discussion and civic engagement do.

Not participating in the electoral process doesn’t address the flaws within the system; it simply removes one’s voice from the conversation.

By voting, you help ensure that the government – our government – remains of the people, by the people and for the people. In a democracy, every vote is a chance to stand up for what you believe in and to shape the world you want to live in. Don’t let that opportunity pass by – vote.

TO NOT VOTE – Haiden Lui, Staff Member

Rich against poor. Black against white. Coke against Pepsi. Apple and Android. Republican against Democrat.

We are surrounded by dichotomies, our ideologies distilled down to clear, simple, shallow choices. Advertisements and endorsements ease our anxieties by doing critical thinking for us, allowing us to simply press a button and seal our fate by aligning ourselves with one choice or the other. This exemplifies the wonderful “Either Or Fallacy” (commonly known as Black or White Fallacy) that plagues American politics and weakens the concept of moderation and balance.

People feel comfortable when in solidarity with others, but such comfort does not come without cost. Political disagreement causes stress within our nation and can result in the destruction or damage of workplace camaraderie or interpersonal relationships.Some voters are reluctant to vote and describe recent American politics as “choosing between the lesser of two evils.” But, we as voters have overlooked an alternative that has always been available: not voting.

High voter turnout doesn’t necessarily ensure that the government represents the diverse voices of its citizens. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 61.4% of eligible voters participated in the 2016 election and 66.8% of eligible voters participated in the 2020 election. America is a representative democracy, not a true democracy. This means that when state representatives are elected, they don’t necessarily represent the true voice of the American people, but rather a soundbite curated through campaigning, corporate lobbying and gerrymandering.

Even with voter engagement, corruption still persists and holds a greater influence over which policies are supported and which are dropped. It is well known that during presidential campaigning, swing states are strategically valuable due to their capacity to turn the tide of the presidential election. It is in these states that the presidency is truly determined. In this sense, the other states are given less importance due to their near-guaranteed choice to support the party they have historically represented, further undermining the claim that every vote counts.

The popular vote is the closest representation of the American people in our political system. However, it is not the deciding factor. Rather, the Electoral College is the final arbiter of the presidential election, which is a committee consisting of 538 electors selected from each of the states. A key detail to notice about the Electoral College is that neither the Constitution nor Federal Law requires that they vote based on the decisions of the popular vote in their state. Rather, it is up to State legislatures to determine if political parties can force electors to cast a certain vote. This means that in some cases, an elector may vote for whomever they desire once elected by popular vote, regardless of what the people desire.

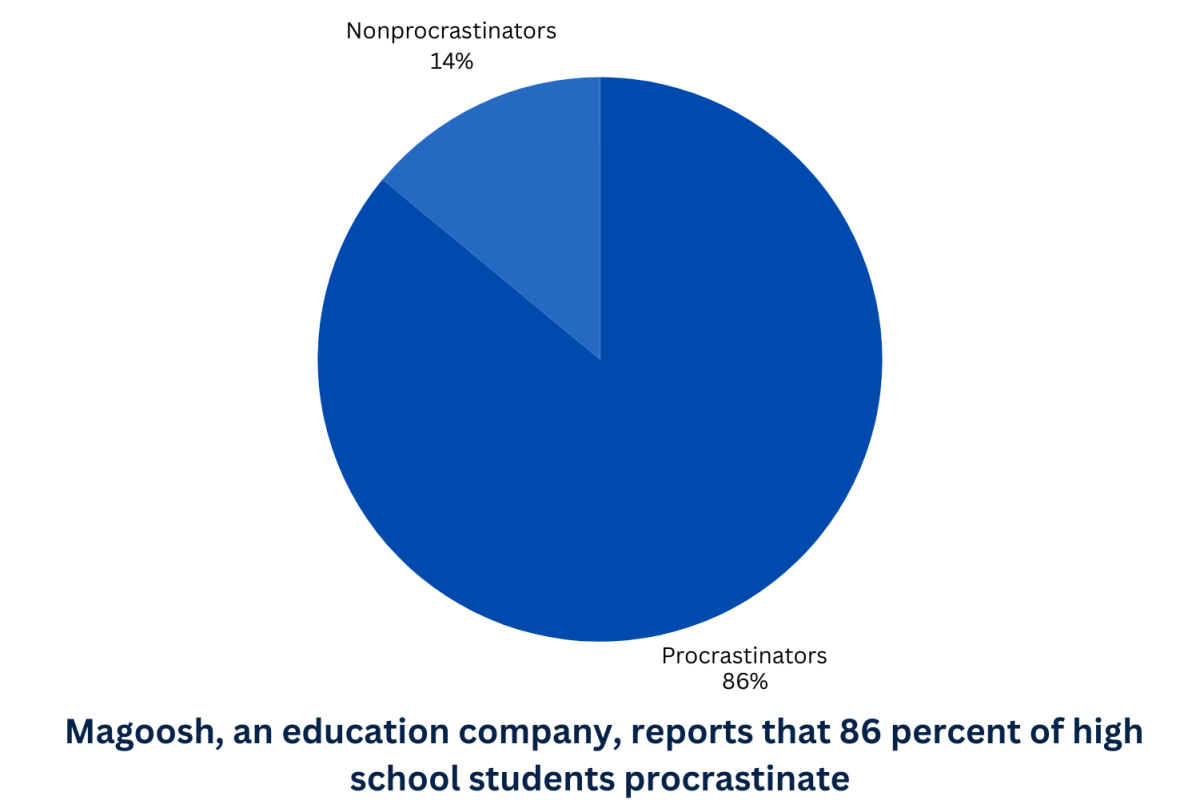

The social stigma surrounding the decision to not vote poses a danger to the integrity of American politics. According to data from the American National Election Studies, over 30% of voters in the 2020 election were misinformed or uninformed about key policies for each candidate. The social pressure to vote has driven individuals to blindly vote based on what people around them have chosen, rather than taking into consideration what policies each candidate supports.

Consider a scenario in which you are part of a kindergarten class and the teacher has decided to host a poll to determine whether she should give the class oatmeal raisin cookies or slices of carrot cake. There are three choices: oatmeal raisin cookies, carrot cake slices, or abstain. Say you vote what your friends have voted for the simple reason that you want to fit in. When the decision is made, you may discover that you dislike carrot cake or oatmeal raisin cookies and feel regretful. Or even worse, you may have made yourself enemies due to your decision. Had you made an informed decision and chosen one option or opted not to participate, you would have felt better and had fewer enemies.

The right not to vote is equally important as the right to vote. Our ability to say “No” and refuse to play the game that is American politics is a powerful tool that upholds the principle of free will. By not voting, you help ensure that the government will, one day, no longer be of incompetent politicians, by gerrymandering, and for corporate interests. Don’t vote.