For many teenagers, high school is all about fitting in. The pressure to conform is everywhere. It exists in the clothes we wear, the music we listen to, the people we talk to, and all too often, whether or not we drink alcohol or do other drugs.

For years now, LHS has been combating the idea that students need to drink to fit in. More recently, this has come in the form of a social norms campaign aimed at proving that the majority of LHS students do not drink alcohol. “Social norms” is centered around the idea that behavioral norms determine the actions of most members of a given social group.

“The theory behind the posters is…if you see that most kids are doing the right thing, that they are not drinking, then you, by virtue of knowing that you fit into the majority, you will not drink either,” said Damian Kulikowski, the LHS student assistance program coordinator.

It’s no secret that the campaign is currently in full swing, owing to the significant amount of posters lining the school walls. From “Mice be like,” to abstract art of a lion’s face to majestic photos of the high school, the fact that 70 percent of LHS students are alcohol-free has practically been drilled into our heads.

But why now? And why such aggressive efforts to get the message out?

“Social norms” started in the Chicagoland area as early as 1998 in DeKalb and eventually made its way to Evanston Township High School. However, it goes back as far as 1986, when Doctor Alan Berkowitz, a licensed psychologist, and Doctor H. Wesley Perkins, a sociology professor, suggested that “social norms” could be used to curb college drinking. Since that campaign found significant success, it has been replicated and piloted in plenty of places, including LHS.

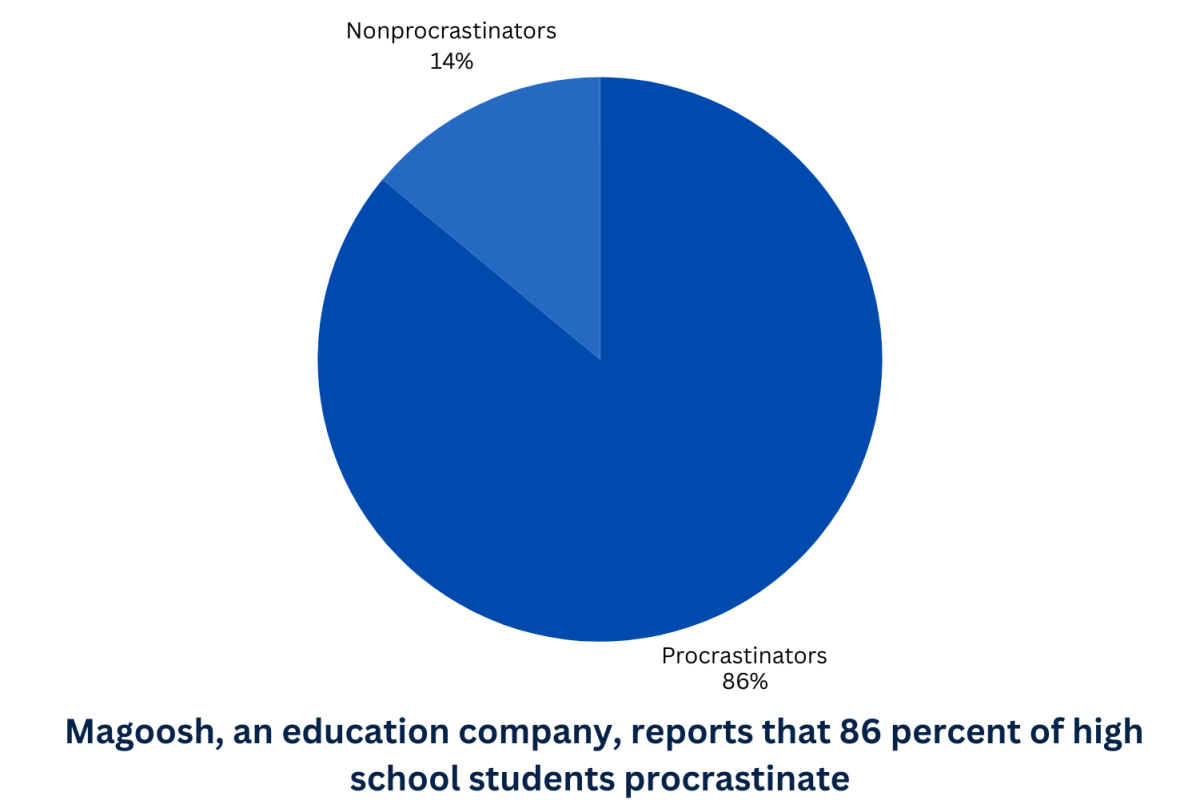

But the question everyone has now is whether or not a difference has been made. Unfortunately for LHS, the program is still young, and no observable progress has been made. If anything, a marginal increase in alcohol consumption has been revealed, with a two percent uptick in drinking since last year, currently sitting at 32 percent.

But to understand these results, we must also understand the data taken. Many of the questions asked in the survey only account for actions done within the last 30 days. According to Mr. Kulikowski, not only did the most recent surveys taken place weeks after Turnabout, a time where students may consume more alcohol than they normally would, but the earliest surveys taken did not happen right after Turnabout. Because of this, it is difficult to observe any legitimate trends between the yearly marginal differences. LHS still has many years to determine this campaign a success or failure.

Another question to consider, though, is why the focus of the social norms campaign at LHS is solely on alcohol. If anything, the survey results are unanimous in the fact that marijuana is also a significant problem at LHS. With 22 percent of the school using in the 30 days before the survey was taken, and 38 percent of the senior class, it only makes sense that LHS should address this problem as well.

According to Mr. Kulikowski, an anti-marijuana campaign is definitely a possibility for the future: “I see [marijuana] as being the new trend. I don’t see that number [of users] going down by any means,” he said.

Beyond just evidence of general use of drugs and alcohol, the surveys have also revealed many other problems within LHS. 10 percent of students have smoked cigarettes in the past 30 days, seven percent have driven while drunk, and 13 percent attended school under the influence in the past year. These are shocking numbers, as are the the 19 percent that have considered suicide. It is clear that LHS has a lot to deal with, as does any other high school, but progress is not an easy thing. For now, curbing alcohol use is where the campaign is starting, but it will be many years before we see where it ends.