As the old saying goes, history is written by the victors. The champions in sports are the ones ultimately most admired and most renowned by fans. People applaud the Michael Jordans and Joe Montanas and denounce the Charles Barkleys and Dan Marinos.

Almost all major sports leagues include some sort of postseason tournament to determine the champion, a king amongst its peers. But is this king truly the best, or just born into the right situation?

Take the 2007 NFL season, for example. The New England Patriots, led by future Hall of Famers Tom Brady and Randy Moss, charged forward to a 16-0 regular-season record, shattering statistical records along the way. The Patriots followed up with back-to-back playoff victories and entered the highly coveted Super Bowl with an 18-0 record, hoping to be the first team ever to reach the 19-0 mark.

On the other side of the field was the New York Giants, who limped into the playoffs with an 8-8 record. Even an outsider with no knowledge of football could see that the Giants would be heavy underdogs to the seemingly invincible Patriots, but looking deeper into New York’s schedule shows that they got hot at just the right time, winning three straight road playoff games. In a low-scoring affair, the Giants shocked the world on the biggest stage and took home the Lombardi trophy, thanks to some gritty play, a touch of luck, and one of the most memorable plays in NFL history.

Former Giants WR David Tyree made history with the “Helmet Catch”.

Does this mean the Giants were the best team? Credit to them for taking care of business, but the Giants appeared to be over-matched in almost every aspect heading into the game. Ultimately, the entirety of the season was decided by one 60-minute event.

As any statistician would suggest, sample size is always a key issue when looking for the best model. In theory, the best way to determine the best team would be to play an infinite amount of games, thus giving a large enough sample size to crown a victor. However, this is impossible simply due to reality — there are time constraints and injuries — so a happy medium should be met between too small a sample size of games and a realistic amount.

College football and the NFL both use a single-elimination type system; if you lose one game in the postseason tourney, you’re out. The NBA and NHL both feature seven-game series, which means that the first to win four games advances. The MLB mixes and matches techniques in its format, with play-in games and best of five- and seven-game series. College basketball presents the most hectic postseason of the bunch. They don’t call it “March Madness” for no reason — the college basketball tournament consists of 68 teams and seven rounds!

Since there can only be one champion, it’s sometimes hard to gauge what the true odds of a team winning it all are. Injuries are incredibly unpredictable, and there is no convenient way to measure factors such as team chemistry and players’ morale quantitatively. Quantum theory will tell you differently, with its intricate ideas of multiple universes, but for our sakes, there will only be one universe and one outcome.

Take the NBA, for example. Only one team out of 30 can win the title, so if all the teams theoretically had an even shot at winning, a fan’s team would only have a 3.33 percent chance of winning. This obviously isn’t how it works, as there are good rosters and bad rosters, along with matchup woes for each individual team. To help get a better model, the basketball simulation video game NBA 2K16 will be used.

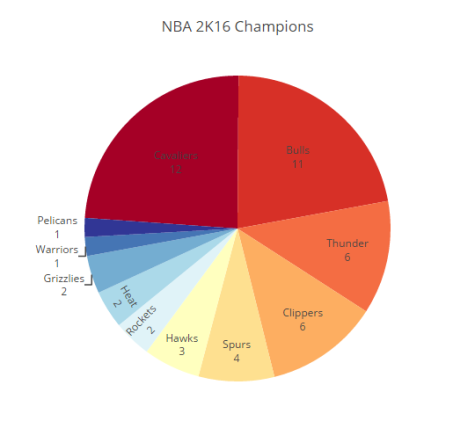

The top contenders by Vegas odds won a majority of the 50 trials.

After 50 simulations of the 2015-16 season (don’t worry, it was not as long as it sounds), it became apparent that the champions were varied. Although there were only 11 unique champions, no team won it more than 25 percent of the time and the results were reminiscent of the projected win probabilities in real life. For example, the Cavs have a 22 percent implied probability of winning it all this year (converted from the Vegas odds as of October 13); they ended up winning 24 percent of the simulations. While 50 simulations isn’t the largest sample size, it does suggest a high variability of potential champions. Despite the low odds of even the contenders and favorites, only one fan base is able to regard itself as champions, and the majority of fans mourn their team’s loss and look to team management for answers.

A counterargument can certainly be made in favor of the small sample size postseason. Playoffs across all sports provide a spark of entertainment and are a step up from regular season slates (in general). When the game is on the line, players are more urgent to move to the ball and give it their all. There doesn’t necessarily need to be a change in the traditional regular season-to-postseason system, because it’s crowd-pleasing with its unpredictability, but it’s important to know the context of the teams’ situations before berating them and getting upset. If you’re upset that your team loses time and time again in the postseason, it probably isn’t much of a reason to get upset, as unforeseeable events play a significant factor. The great Ricky Bobby might have said, “If you’re not first, you’re last,” but not everyone can be the champion.