While most students in AP classes who take the AP exam as well as seniors who hold an A may exempt from their second-semester final exams, other high-achieving students are snubbed.

Year after year, students at Libertyville High School with high grades in their classes are forced to study for and sit through meaningless yet draining finals. Kids with high A’s whose grades have no chance of changing letters because of the final are still mandated to take cumulative exams at the end of each semester. This phenomenon must stop.

One prominent argument for final exams in high school is that they prepare students for college. After all, many colleges and universities have traditionally used final exams as a way to determine large parts of students’ grades.

“I think the reason we’ve stayed taking finals so long this way is because we feel it prepares you for college,” said LHS Principal Dr. Marina Scott. “So I’d really be interested to see how many finals are given in college.”

As it turns out, college finals are on the decline. According to recent data, only 259 of the 1,137 undergraduate courses at Harvard, a leader in education that other institutions are likely to follow, had a scheduled final exam last year.

“Across the country, there is growing evidence that final exams — once considered so important that universities named a week after them — are being abandoned or diminished, replaced by take-home tests, papers, projects, or group presentations,” wrote reporter Keith O’Brien for The Boston Globe.

In addition, a dean from the University of Albany SUNY believes that exams can be arbitrary and inauthentic benchmarks for what students learn in a course: “If you looked at a lot of final exams in courses you’d think, ‘This is not a very valuable standard.’ These tests ask the kind of questions that students may never be asked again in their lives, in detail that they may never be asked again in their lives,” Robert Bangert-Drowns told collegedegrees.com, a blog that comments on college education.

That’s why the LHS administration is opening up a broader discussion about finals.

“Right now the district is putting together a committee about finals,” said Dr. Scott. “The reason we give finals the way we used to is because we’re locked into that time period. Maybe we need to free ourselves from that time period. Maybe it doesn’t have to be that last week. Maybe it’s just one other assessment. Maybe teachers get more choice. Maybe you get more choice whether to take it or not.”

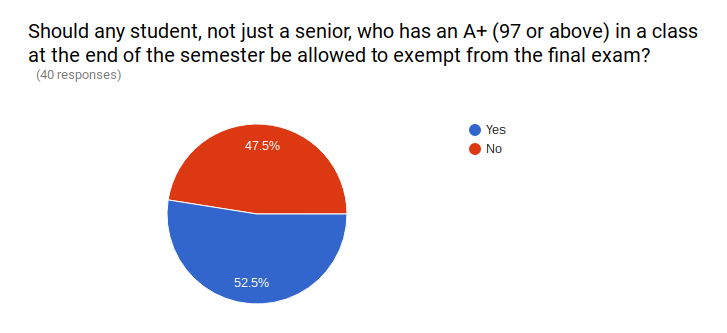

A slight majority of faculty who responded to the survey conducted for DOI on this topic supports the idea of finals reform for students with high A’s. Most teachers who agreed with the idea wrote that students who have high A’s have shown clear mastery of skill in a subject. However, the most common argument from teachers against exemptions for students with high A’s was that the cutoff for an exemption would cause turbulence.

“[A kid who’s] got a 97 [percent] is probably a good enough student where they don’t need to bother taking a final, but on the other hand, does a 96.5 then qualify? Are we going to be opening a whole other can of worms with students trying to reach the 97 rather than just trying to get the most out of the class? I don’t know,” said Mr. Bill Mix, a geography teacher for more than 20 years at LHS. “I think 97 percent–I mean that’s fine, but why not 90? Why not if you already have an A in the class? What about those kids who get an 85 in the class and can’t possibly move up or down?”

While Mr. Mix may be right that a strict cutoff at a 97 percent would be controversial, this is impossible to avoid with any cutoff, including LHS’s current grade cutoffs. What constitutes an A, B, or C is often hotly debated; some draw the line for an A at 90 percent, but other staff members say 89.5 percent or even 89 percent. The same would inevitably be true for a final exemption cutoff. But Mr. Mix also offered another observation about placing a cutoff at 97 percent.

“Would you say that a 97 percent in Honors Geography is the same as a 97 percent in Mr. Mark’s AP Physics class? I don’t think you’re comparing apples to apples,” he said.

A 97 percent, however, is a significant achievement regardless of the level of the class, and current letter grades don’t take into account the difficulty of a course. And, although Mr. Mix and some other faculty members question the idea of finals exemptions for high-achieving students, this exemption policy still has significant support. In fact, 52.5% of the respondents to the survey sent to LHS staff on this idea said they would support such a policy.

Change, however, may be slow to come. Despite endorsement among faculty and the existence of the current district committee, the process of approving and adopting a policy that would challenge long-held academic traditions is long and arduous; it could take years due to the complicated nature of this issue.

However, regardless of the time it takes to implement new finals policies, it is absolutely imperative that change occurs so that students have more incentives to do well and so that hardworking students are no longer punished for their scholarship.