Though sexual assault is often taboo, and not talked about in high schools, this stat has proven that sexual assault is incredibly prominent among teens.

What Goes Unsaid

sexual assault: illegal sexual contact that usually involves force upon a person without consent or is inflicted upon a person who is incapable of giving consent (as because of age or physical or mental incapacity) or who places the assailant (as a doctor) in a position of trust or authority.

Depression. Embarrassment. Self-blame. Powerlessness. Anger.

These are just a few of the horrifying feelings victims experience after being sexually assaulted. And yet, often no one will know that it even happened. The situations are taboo; a hush-hush occurrence where, through a combination of shame and guilt, 70 percent of sexual assault cases go unreported, according to the Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network, or RAINN.

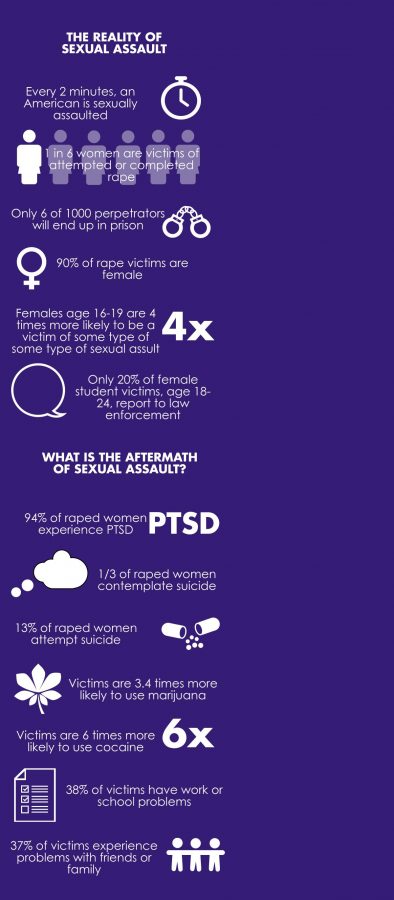

According to RAINN, in the United States, there are about 288,820 victims of sexual assault per year. The most common time for someone to be victimized? During their teenage years and while at college, where the rates are three times more likely, but where only 20 percent of cases are reported.

With that being said, it’s clear that the topic of sexual assault is incredibly important to talk about and understand, especially for teenagers in high school. So why is it rarely mentioned?

WHAT DO STUDENTS THINK?

“That physics test raped me.” “I just got abused by my in-class essay.” A variation of these phrases may be heard by students while walking through the halls or sitting in class on an average day in school.

All too often, high school students degrade sexual assault, not thinking twice about it, when in reality, these phrases are unjust and hurtful.

According to health and physical education teacher Mrs. Joyce Amann, sexual violence is taught throughout the health curriculum that each freshman goes through. About 3-4 days of the sexual health unit are dedicated to talking about violence, as are a few days at the beginning of the semester when talking about mental and emotional health and during the drug and alcohol unit. Students learn what makes a relationship abusive; setting their personal limits and how to stay safe; overcoming abuse and how to get help; and other information, said Mrs. Amann.

After freshmen take a health class at Libertyville High School, sexual assault is rarely mentioned again until the end of senior year during an optional campus safety session done by the College Resource Center.

The lack of comprehensive education about sexual assault throughout high school can lead to students talking about it in a demeaning way and also not understanding the true issues that come with it. Sure, everyone can say “sexual assault is bad,” but do students really know anything beyond that?

“All you really learn about [sexual assault] in health is to tell an adult [when it happens], and there’s no real education about what you should do if it’s happened to you in the moment or the effects of it,” Advocat member and junior Colin Hawkinson expressed. “I feel that in order to make students more aware of it, make it a bigger topic in health or gym class.”

This absence of an ongoing sexual assault education could lead students to think that these cases are not taken seriously at LHS, or that there is no one that they could talk to, nowhere to go to, and nowhere to obtain support when dealing with a case of sexual assault.

“Honestly, I didn’t even know that I could report [sexual assault]. I don’t know how to report, or what would happen if I reported it. So, I think the school should advertise more: this is how you can report if anything is happening and this is what we’ll do,” Advocat member and junior Grace Schamberger stated.

With a graduation level of 96 percent at LHS and only 4 percent of people living below the poverty line, Libertyville has proven to be a pristine and privileged community. However, sexual assault still shows its prevalence here, not just in at-risk neighborhoods, countries, and college campuses. Take, for example, a junior at LHS (who will remain anonymous for confidentiality reasons) who was raped as a high school student.

“I think [that sexual assault] needs to be more talked about, but also less talked about, if that makes sense. The way that people talk about is wrong, and the way that it should be talked about is not really brought up. People are talking about [sexual assault] as if they know about it, and it’s kind of derogatory when it comes up,” she stated.

She also expressed that whenever sexual assault comes up in a conversation, as a joke or seriously, she “kind of just walks away” because most people are uneducated about the topic and can be offensive or uncensored, whether they mean it or not.

At LHS, many serious issues are given a lot of attention: promoting being drug free through Red Ribbon Week and symbolizing suicide awareness and prevention through Yellow Ribbon Week are two recent examples that will begin to occur annually. However, sexual assault is rarely mentioned or talked about.

Schamberger agreed that sexual assault isn’t talked about as much as other issues within the school: “I think [sexual assault is] just as important and damaging as any other types of abuse that are paid more attention to in school, and I don’t understand why.”

WHAT IS ADMINISTRATION DOING?

The administration and LHS staff members agree with students and believe that sexual assault is a taboo topic that needs to be addressed more throughout students’ four years.

“I feel like in this country, talking about sexual violence is something that we really shy away from. I think that part of it is that we have pretended, for a long time, that it just doesn’t exist. I also think that because there is such shame around sexual violence, that people who are survivors do not come forward,” said Ms. Jennifer Andersen, the G-P LST social worker.

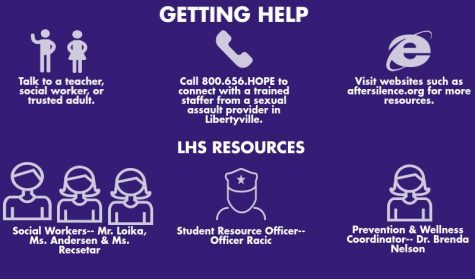

As of right now, there are various components of dealing with a case of sexual assault at LHS. Each LST has a social worker who is trained and is able to aid those affected by issues including sexual assault—Mr. Greg Loika in the A-F LST, Ms. Andersen in the G-P LST, and Ms. Lindsay Recsetar in the Q-Z LST.

According to Ms. Andersen, when a student comes forward with a case of sexual assault, they are referred to their LST social worker. Some students may want to keep it confidential, keeping the situation between them and their social worker; some may want to speak to their dean to get more support; and some may want to get involved with the Student Resource Officer (Officer Dusan Racic), and press charges against their assailant. The choice is up to the student.

However, instances of sexual assault are dealt with on a case-to-case basis. According to LHS principal Dr. Marina Scott, when a case of sexual assault happens on school grounds—for instance, during a class or a sport—the school must step in because it is their “duty as a school to intervene and create safe spaces for students.” If something were to happen off of campus, it is that student’s own responsibility to seek LHS staff to obtain the help that they need.

In order to reduce the taboo nature of sexual assault, the LHS administration is gearing towards adjusting and implementing certain programs to reduce the stigma around the topic.

As stated by Dr. Scott, the administration is hoping to implement a program called Green Dot in the future. With this, the whole LHS campus would be pictured on a hypothetical map. Wherever any type of violence occurred (and was reported), whether sexual, emotional, or bullying, a red dot would pop up in that spot. On that same map, there would be green dots where a bystander responded in a positive way, such as by restricting the behavior, or by talking to the person who was affected. The program has not been completely planned out, but the LHS administration is hoping to put every student and staff through some form of training to educate them about being a bystander in any case of violence.

Though the process of implementing this program is intricate, and requires training of all LHS staff and students, it is something that the administration hopes to execute in the future to help fight violence in school and educate students about coming forward in these types of situations, whether as a person being abused or just as importantly, as a witness.

“When you hear the presentation [of sexual assault] in terms of victim or perpetrator, you can say, that’s not me, that’s not me, but the bystander, you can’t say that’s not me, because [you] need to keep [your] eyes and ears open ‘cause [you] could be the person who helps someone,” Dr. Scott expressed.

WHY TALK ABOUT IT?

As LHS students prepare for their journey to college, knowledge on sexual assault is critical. According to the Association of American Universities (AAU) and RAINN, one in every five-to-seven males will be sexually assaulted prior to leaving high school, and one in five women in college will be sexually assaulted. Therefore, not being 100 percent sure on what to do in case of a situation of sexual assault can be devastating.

In Libertyville, many diminish the severity of sexual assault and never truly learn about how to react to a situation or even how to prevent it from happening in the first place. “If anything like that had happened to me [in high school], I wouldn’t know where to report it or who to talk to,” exclaimed Shannon Roche, a Class of 2015 graduate of LHS now at the University of Vanderbilt. “I didn’t know how prevalent it was in college and how many women are affected by it.”

Many colleges around the United States have online programs on how to prevent sexual assault and what to do if someone is harmed, including Indiana University, Vanderbilt, the University of Wisconsin Madison and others. According to Roche, who had to take an online course about sexual assault prior to registering for classes, there are also several resources students can use on campus, such as rape crisis centers and 24/7 support systems.

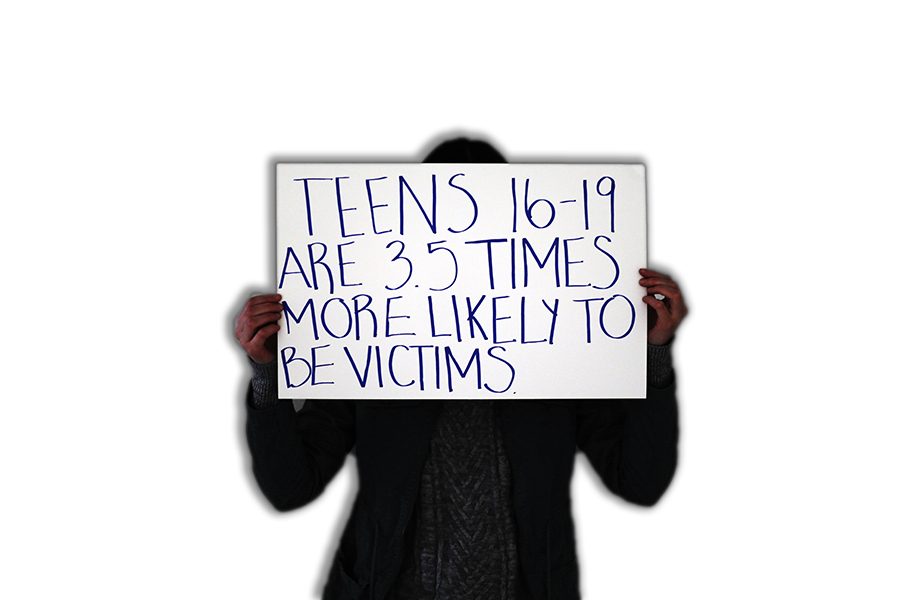

However, even if the resources and knowledge become well-known throughout college (which isn’t always the case—a campus climate survey in September 2015 by AAU showed that out of 150,000 students from 27 participating institutions, 75 percent of them were not aware of the school’s resources), high school students can be unprepared on how to respond to sexual violence. According to the National Sex Offender Public website, teens ages 16-19 are 3.5 times more likely to be victims of rape or sexual assault, an age group right at the peak of high school. It is logical to assume that it is tougher for students to respond correctly to sexual assault if there isn’t much knowledge on the subject.

Although college is the next step for many LHS students, sexual assault doesn’t just magically end after that and has continued to prove its prevalence through recent events. The topic of sexual assault has been extremely publicized lately as president-elect Donald Trump was accused by 11 women of sexual assaulting them. Stanford student and Olympic swimming hopeful Brock Turner was also convicted of sexually assaulting an unconscious, intoxicated woman, spending just three months behind bars. A controversy around his case erupted and was focused on his sentence time; many believed he deserved a much longer sentence than what he was given, and this sparked national outrage.

Even at LHS, sexual assault was a heated discussion recently with the school’s response this past summer to an alleged incident of sexual assault during a 2015 water polo postseason match. Former McHenry High School water polo player and current sophomore at Monmouth College Rebecca Dabrowski alleged that an LHS player sexually assaulted her underwater during the game. Two days after the incident, the Buffalo Grove Police Department started an investigation, but the case was closed without any charges. District 128 never conducted its own investigation, saying that they waited for the police investigation to finish and by the time it was over, they “no longer had jurisdiction of the student” because the alleged assaulter had graduated.

These incidents demonstrate that sexual assault has proven to be very relevant, both nationally and in Libertyville. Just because sexual assault is taboo in high school does not mean the problem doesn’t exist.

**Sexual assault is nothing to be ashamed of, and if you are a survivor or are fearful for a friend, tell an adult you trust or talk to a social worker. They are always there to be of assistance and help in any way. The infographic to the right of this can provide you with resources available online, and at LHS.**

Sexual assault stats infographic made by Becky DeAcetis. Getting help infographic made by Matthew Price.